Ireland's COVID Response, Part 1: Count Your Blessings

Ireland performed surprisingly well in terms of deaths

Note: This post is first in a four-part series on Ireland’s COVID response. Any fact that isn’t linked is sourced from the book Pandemonium: Power, Politics and Ireland’s Pandemic.

How did Ireland fare against COVID-19? This series is my attempt to answer that question. I am bound to have made errors; please email any you spot, and feedback more generally, to fitzwilliameditors [at] gmail [dot] com.

1.1. Ireland compares favourably with other countries

At a cursory glance, Ireland did relatively well in the pandemic. Measured by confirmed deaths, Ireland compares favourably with its European peers: 148 per 100,000 individuals versus 245 for the EU as a whole. Measured by excess mortality, the picture looks better. According to the Economist, Ireland has had 88 excess deaths per 100,000 individuals since 1st January 2020, compared to 145 for Germany, 225 for the UK, 270 for the world as a whole, and 370 for America. Northern Ireland doesn’t appear in their dataset, but suffice to say, Northern Ireland performed like the rest of the UK and not like Ireland.

‘Excess mortality’ is not an attempt to more accurately measure how many people died from Covid. It’s hard and perhaps impossible to say what counts as a Covid death. Excess mortality measures how many people died that would not have died if the pandemic hadn’t occurred. If you get sick of staying at home and go out and shoot your neighbour, and you wouldn’t have otherwise, then that’s an excess death.

Ireland’s excess mortality rate is lower than the death rate from Covid. This is not because the world was safer for other reasons, like that people were driving less – that effect was small. It’s because Covid increased the total number of deaths, but also, many deaths that would otherwise have occurred happened because of Covid instead. Covid killed many elderly and ill people who otherwise would have died from some other cause in just a few months.

Ireland’s low death toll came at a great cost: between March 2020 and January 2022, Ireland had the harshest public health measures in the EU or UK for four months. Irish measures were always among the harshest few. At its apex, Irish people were not allowed to travel more than two kilometres from their homes. It was grim.

It’s hard to properly grasp the sheer social cost of lockdowns. While there has been a lot of research on the effects of the pandemic on mental illness, research on how much worse it made the median person’s life is distressingly thin on the ground. The UK has national happiness statistics, which show large declines in wellbeing, which I expect generalise to Ireland. Suicides mysteriously declined during Covid, but for various idiosyncratic reasons, I don’t believe that suicide is a reliable proxy for unhappiness. What you really care about is how much worse a month under lockdown was compared to a month pre-pandemic. I can’t believe I’m saying this, but I really can’t find anything better than Bryan Caplan’s Twitter poll. It finds that people are indifferent between living ten normal months and a pandemic year. That poll was about Americans, so I naively expect the Irish situation to be even worse.

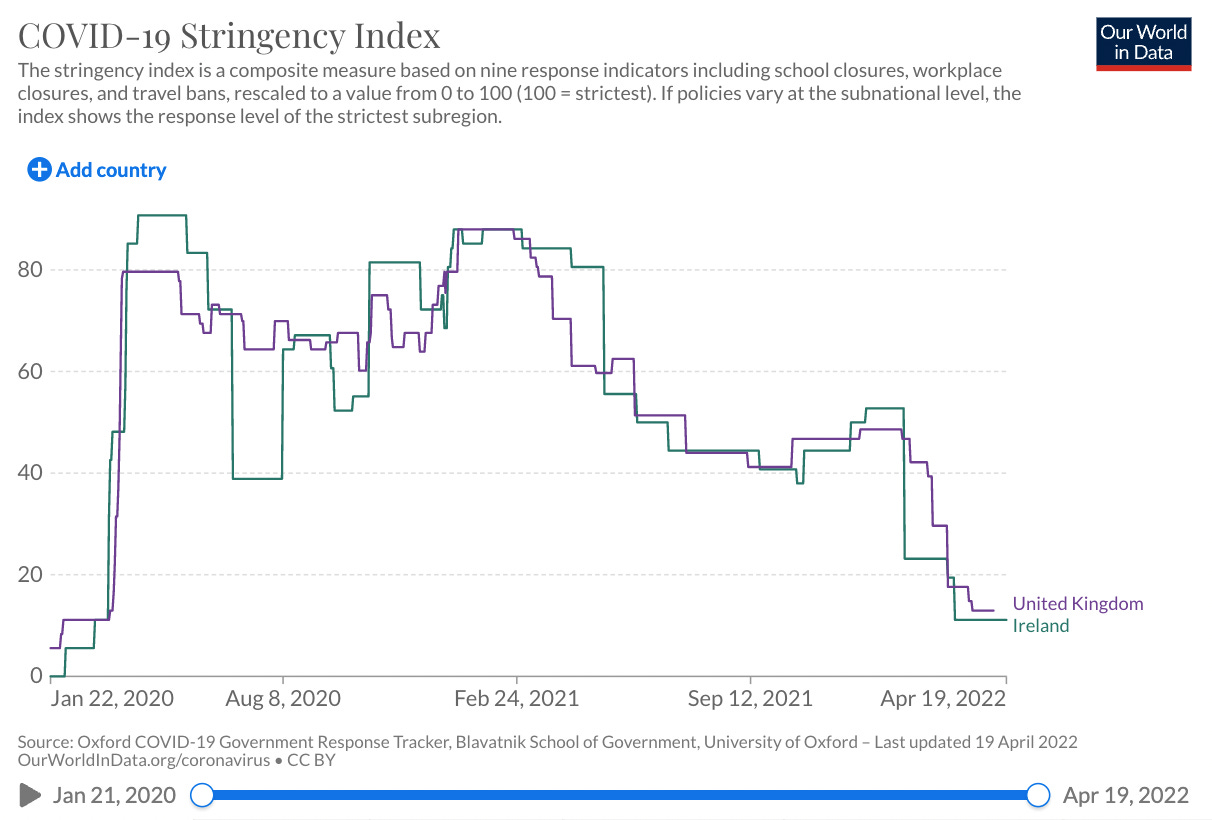

Ireland and the UK are so similar; what accounts for their differences in outcomes? It’s hard to say. Ireland and the UK at all times had similar restrictions as measured by the Covid stringency index. This index is a 0 to 100 scale which combines responses including school closures, travel bans, testing policy and face masks. Like all indices, we shouldn’t put too much stake in it, but commentary from Ireland about how the UK had opened up was greatly exaggerated. When restrictions vary at a sub-national level, the stringency index represents the strictest region. Scotland had harsher Covid rules than England, but still, Scotland only barely performed better in terms of deaths.

Even Ireland and Northern Ireland had very different Covid outcomes. An account of the pandemic based on age, population density, or culture will have to contend with why the situation was so different north and south of the border. In a blog post, Scott Sumner hypothesised that cultural heterogeneity is a key variable in explaining cross-country outcomes, e.g., Belgium did unusually poorly because of being culturally disunified. Might this apply to Northern Ireland?

1.2. Compliance with the restrictions was high

In some countries, the war against Covid was over before it began, but not so in Ireland. Irish people mostly followed the restrictions and there was never any major social unrest. The one instance of the public seriously rebelling against Covid rules was Christmas 2020, when there was widespread socialisation.

During the pandemic, Irish people were generally trusting, and there weren’t many cranks trying to peddle bogus cures or anything. The great Irish Covid triumph was that vaccine uptake was rapid and sky-high, at some points higher than any non-tiny country in the world. 81% of the entire population is now fully vaccinated (94% of adults). Trust in credentialed authorities in Ireland is high, and I will discuss some of the downsides of this later. But one upside was the tremendous willingness to get vaccinated.

Ireland is so small that there wasn’t a lot of need for different regional approaches. County Kildare had a several-week lockdown in connection with an outbreak at a meat plant (there was a handful of these in Summer and Autumn 2020). Dublin sometimes had harsher restrictions than elsewhere, it being by far the biggest population centre and source of international travel. I have no idea how I would assess the efficacy of these local lockdowns. A place to start would be Sharma et al, which looked at the effect of restrictions during the second wave in Europe at the sub-national level.

1.3. Everyone involved behaved ethically

I’ve previously written about how and why some places become ‘ungovernable’. Various theories point to the proliferation over time of different interest groups. But another cause is that being a politician has become unbearably unpleasant. The ranked-choice voting system insulates Ireland from some of the worst political nastiness of other countries (one less vote for your opponent is not necessarily one more vote for you). But the nastiness has been copied from elsewhere, and social media has made the government’s every deliberation visible. I can write all day about what someone should or shouldn’t have done, but ultimately, those involved in the Covid response had a near-impossible job, and I wouldn’t have done any better.

But also, this is a cop out. Ideally, doing the right thing would be the path of least resistance.

1.4. The government and public health have a complicated relationship

The National Public Health Emergency Team (NPHET) is a group convened by the Minister for Health when there is a public health crisis. During Covid, NPHET was chaired by the opinionated and steadfast Tony Holohan, who had various public disagreements with the government. NPHET was a rotating cast of characters with several advisory subgroups, notably including a group of coronavirus experts and a modelling group.

To say that there was imperfect coordination between the different players in the Covid response would be an understatement. There were several cases of politicians reporting conflicting information about the government’s plans. In one instance, Tánaiste Leo Varadkar and the Minister for Health reported completely different information about their relationship with NPHET. There were also cases of some relevant stakeholders only finding out about an important change in policy through the media, e.g., the head of a union only finding out about new restrictions that affect her through the Irish Times the next morning. Sometimes this was just because of ministers working late into the night and people being uncontactable. On occasion, serious problems came about because of public servants’ unwillingness to work weekends and evenings. On 11th February 2020, the Chinese embassy tried to contact the Health Service Executive (HSE) about a potential Covid case, and noted that they were “concerned” that they weren’t receiving responses to their emails after 1pm on weekends.

The relationship between NPHET and the government began to fray in October 2020, when, for the first time, they didn’t follow a major piece of NPHET advice. NPHET recommended a swift lockdown, but the government delayed for two weeks. This ensured that, when they finally did lock down, it was harsher and longer than it otherwise would have been. The same thing happened that Christmas. A failure to lock down more harshly at Christmas in part contributed to a tremendous spike in January 2021, though this was also driven by the Alpha variant.

NPHET was surprisingly clandestine – even the Minister for Health was not allowed to sit in on their meetings. Public health advice was formulated in secret, often leaked, and then presented to the government, who had to make decisions under great pressure to follow the leaked advice.

[Edit: At this point, it’s worth mentioning the importance of insulating public health advice from politics. One of the reasons that public health institutions might be excessively risk-averse is that they fear they will face negative consequences for making judgements for which they can be blamed. Several problems of the early pandemic were problems of too little accountability, in the sense that no single individual or body was responsible for some aspect of pandemic response. But politicisation is, in a sense, a problem of too much accountability. Scientists should never face negative consequences for giving the best health advice they can.]

Covid decisions involved lots of office politics and clashing personalities. There was a lot of attention paid to who was undermining whom, who was contradicting whom, and who was on the side of The Science (hint: whoever disagreed with you wasn’t following The Science). My conclusion is that more people should just decide what would be a good thing to do, and then do that thing.

1.5. It’s almost impossible to know whether lockdown worked

We can only take educated guesses at which Covid policies worked. You can’t just look at whether more locked-down areas had less spread. In the language of econometrics, infections are endogenous: we would expect harsh restrictions to be introduced in precisely those areas where infections are high. You also can’t just look at whether a more locked down area subsequently had less spread; this doesn’t establish whether the lockdown caused the reduction in spread. Differences in testing across countries mean it’s hard to compare which measures reduced infections, and differences in reporting standards mean the same thing is true of deaths. Ireland counts any deaths that occured while the person had Covid (or is likely to have had Covid) as a Covid death, “unless there is a clear alternative cause of death”. This is internationally quite an expansive definition.

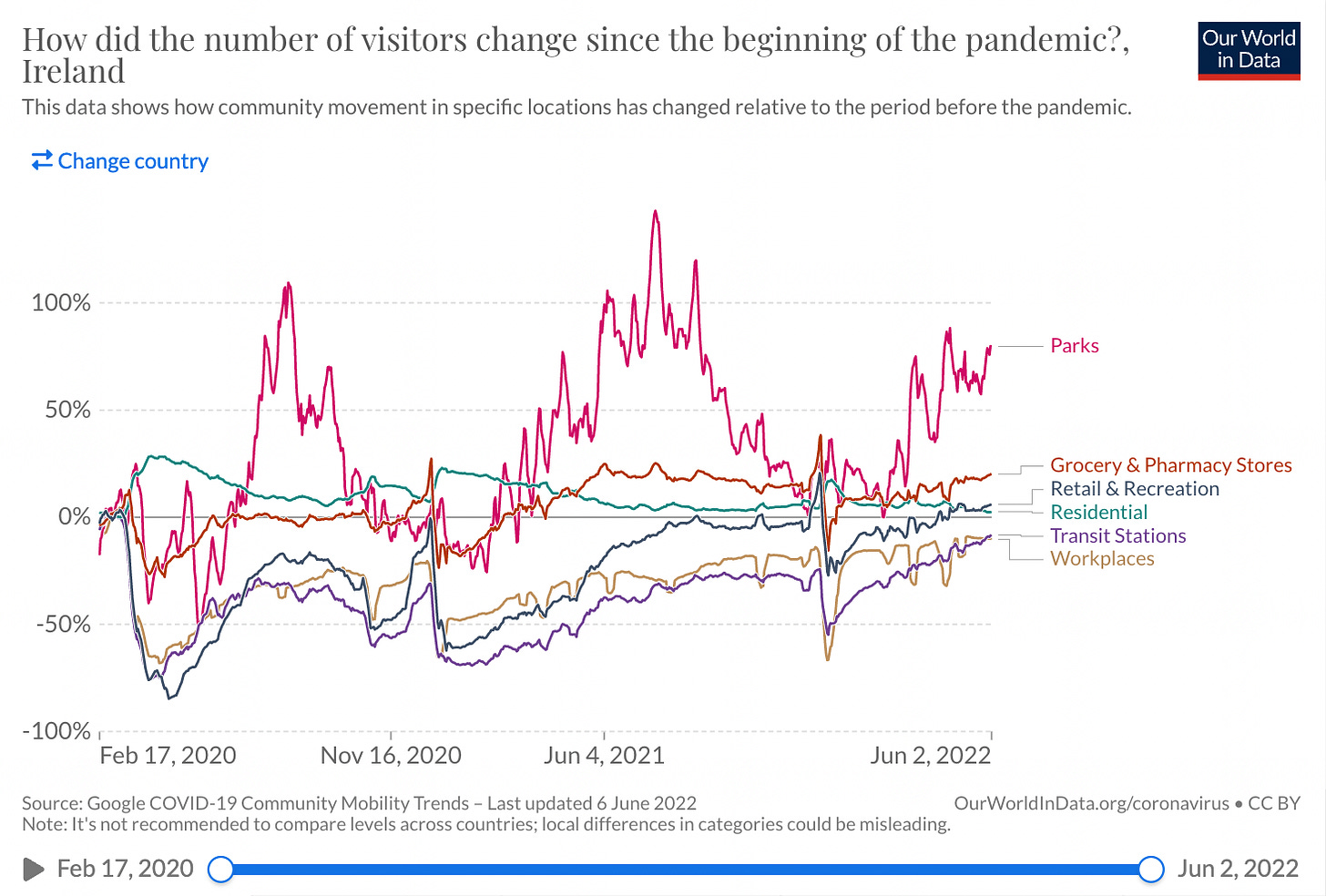

Perhaps the largest methodological problem of all is determining how much of the reduction in spread came from state coercion and how much from voluntary behaviour change. When there was more Covid, people socialised less, all else being equal. One thing you can do is look at socialisation before and after a measure was introduced and see whether the measure affected the previous trend. But this is tricky. You can generate lots of convincing-looking graphs that show X having no effect on the trend of Y, but maybe X was needed just to keep Y on its previous trajectory. Hence, the age-old question: does reality drive straight lines on graphs, or do straight lines on graphs drive reality?

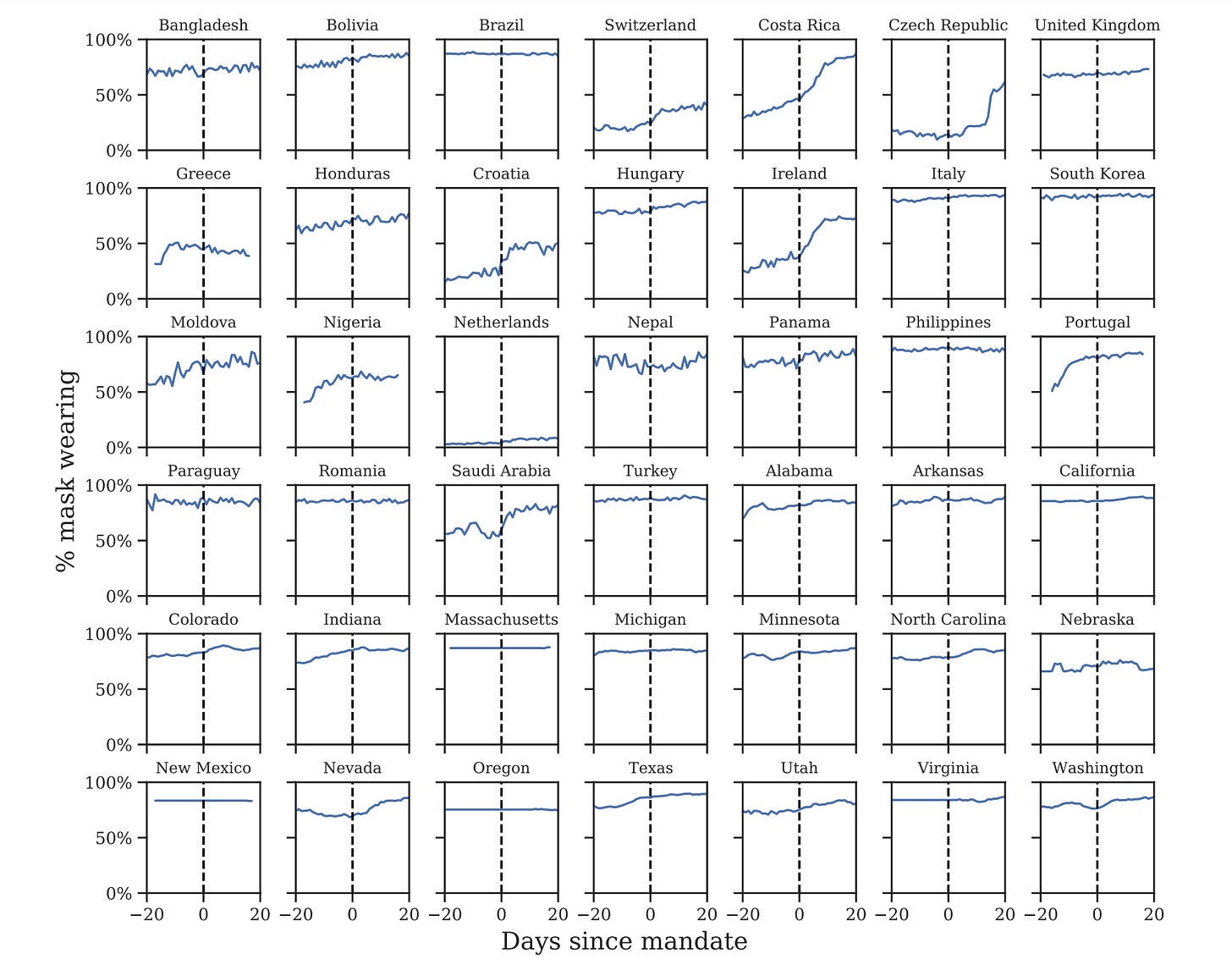

Leech et al compare mask-wearing before and after masks were made mandatory in various states and countries. It finds that, in most places, mask mandates had minimal effect. Interestingly, Ireland is just about the only country studied for which this isn’t true. But the point is, there’s no way you could identify when different measures were introduced just by looking at the graph of behaviours. Even when mask mandates appear to be effective, it may only be a small number of individuals who are masking up because they have to; the rest could just be following the crowd. This makes the task of assessing lockdown effectiveness almost impossible.

I would hesitate to say that most behaviour changes were voluntary throughout the pandemic. But there’s a much greater willingness to endure sacrifice to stop the spread of disease than I previously imagined, and this cultural solidarity is very strong in Ireland in particular. This is curious, because, despite the sacrifices, there was little appetite for relatively minor structural adjustments. It’s only a slight caricature to say that Irish people were willing to live under house arrest for two months before they were willing to wear masks. Air filters weren’t rolled out in schools until January 2021. Many activities were slow to move outside. Even some of my most cautious friends were not testing regularly once tests became widely available, apparently preferring to stay inside and wear a mask to achieve the same level of safety. This is an aspect of human behaviour I still don’t remotely understand.

Sam Enright is executive editor of the Fitzwilliam.

It's not clear to me that your explanation of why 'everyone behaved ethically' is correct, not least because not everyone actually did behave ethically: the Golf Society scandal happened very early on! I think a better explanation is gotten by comparing that scandal to the UK's two superficially similar scandals: unlike the Dominic Cummings–Barnard Castle affair, the Golf Society scandal involved very many people organised together, and thus could not just get written off as the poor judgment of a single individual; unlike the Downing Street parties, the Golf Society trip happened very early into the pandemic. I think these two facts helped the scandal put the fear of God into the rest of the country's politicians for the rest of the pandemic (it was clearly institutional, so politicians now had to actively extricate themselves from the attitudes of the Golf Society; and it happened so early there was no time for huge amounts of unethical behaviour to occur beforehand). And I think it's the impact of this particular scandal, rather than anything general about social media, that explains why in general Irish politicians did not get caught in any major scandals after 'Golfgate'.