Ireland's COVID Response, Part 4: The Definition of Insanity...

What have we learned?

Note: This is the final part of a four-part series on Ireland’s Covid response. I recommend you read parts one, two, and three first. Any facts not linked are sourced from the book Pandemonium: Power, Politics, and Ireland’s Pandemic.

Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

-Attributed to Einstein (falsely of course)

4.1. The phrase “no evidence” is bad science communication

Tony Holohan repeatedly stated that Ireland shouldn’t adopt mass testing because there was “no evidence base” to support it. This was not the first time he and others on NPHET had bandied about the phrase “no evidence” where it didn’t belong. There are three extremely different definitions of the phrase “no evidence” that were used during the pandemic:

There are no randomised control trials or peer-reviewed scientific papers about this exact topic.

Reasonable people can disagree about this, but I don’t believe it, and there is not some obvious single empirical variable it rests on.

We know with high confidence that this thing is false.

And nobody clarified which of these three they meant! Here’s an example of each definition of the phrase being used in context:

“There is no evidence that masks work.” (Read: there are not yet high-quality studies about this specific question.)

“There is no evidence that mass testing will work in Ireland.” (Read: some people believe this but I don’t and there’s no single empirical variable it rests on.)

“There is no evidence that Bill Gates is microchipping you.” (Read: this is false.)

NPHET used all of these definitions interchangeably without saying which one they were talking about. The Irish Times lapped it up too: here they are using definition #1. Here they are using definition #2. And here they are using definition #3.

The phrase “no evidence” was also often used in the debate about First Doses First. If a vaccine is tested in a room with the walls painted red, it’ll still work in a room where the walls are painted blue. You’re not allowed to just say that clinical results don’t generalise outside of the context they were conducted in. Some things are irrelevant and some things are relevant – you need to have a causal model. For example, the fact that ‘fractional dosing’ has been used for many other vaccines in the past is surely relevant. It is also surely relevant that the Phase III trials were designed to get the vaccines out quickly, and not because anyone involved particularly thought that a four-week interval would generate the best immune response. Whether we should stretch the doses out longer doesn’t hinge upon the results of one specific paper. The world almost never works like that.

NPHET also claimed in the early days that there was “no evidence” that masks work. There were in fact several pre-pandemic papers on the efficacy of face masks, albeit of low quality (ethics rules mean that randomising who gets a mask and who isn’t allowed). But that’s not really the point. NPHET failed to have remotely sensible Bayesian priors, i.e. initial probabilities which are updated when new information comes in. Your prior belief that physically blocking the flow of particles would impede the spread of a respiratory illness should be very high. For me to be convinced otherwise would require several high-quality studies show null or negative effects. It is simply not rational to be totally agnostic.

4.2. Being told to “follow the science” isn’t helpful

In some countries, the Covid conversation centred around “following the science”, and the government’s failures were often blamed on not following scientists’ advice. But this narrative isn’t so applicable to Ireland: from March to October 2020, politicians followed nearly every word of their scientific advisors. The structural failure was a level deeper. Now, I am not devaluing expertise. You cannot overstate the importance of knowing stuff, as opposed to merely pretending to know stuff. But it is often not obvious who has expertise over what. Consider the doctors who advised against mask-wearing to conserve masks. The person who has expertise over this is someone who knows a lot about the supply chains of medical products. In many of these contexts, doctors or “experts” had little advantage over generically smart individuals.

An excruciatingly narrow definition of “expert” was on display when NPHET scoffed at the endorsement by Nobel laureate economist Paul Romer of Mark Ferguson’s report to the government on antigen testing. Romer is an extremely smart man and he was thinking about these issues since the start of the pandemic. NPHET’s dismissal of him was sheer hubris.

There are a few fundamental problems with being told to “follow the science”. The first is that the fields involved in answering questions about the pandemic can only be called “science” under extremely expansive and generous definitions of science. Epidemiology is frankly dubious. Economics has hardly answered questions about lockdowns definitively. In the case of certain political and moral issues, such as human challenge trials, I suspect that public health experts’ beliefs are just barely correlated with reality.

A second problem with “follow the science” is that it produces a false sense of certainty. I was told by a nurse recently that the reversals in government policy were only noticed by highly attentive and educated people. But you hardly need a PhD to see that “masks don’t work, but we also need to conserve masks for healthcare workers” doesn’t make any sense. Or to be disturbed by the many sharp turns in policy that were not accompanied by admissions of error or uncertainty. They were “following” the “science” all along, of course.

The even less helpful phrase was “trust the science”. Trust undermines science, it doesn’t reinforce it. The media would often report that some bold and controversial claim was true “according to studies”. Little attention was paid to whether that question could be answered with “studies”, whether those “studies” were representative of the scientific literature as a whole, and whether the studies had requisite statistical power to answer their intended question even in principle. And all of this generously assumes that the evidence wasn’t just completely misrepresented.

4.3. We fought the last war

The four countries with the largest number of US troops are Germany, Italy, Japan, and South Korea – in other words, the Axis Powers in World War II, plus Korea. This is often mocked as a fairly literal expression of the phrase “fighting the last war”.

As far as I can tell, this is approximately the current state of the public health establishment.

The last pandemic was the 2009 swine flu (H1N1) outbreak. Several of the measures taken by Western countries would have been sensible in the context of an influenza pandemic, but not in the context of a coronavirus pandemic. Influenza spreads virulently in schools, and several countries enacted school closures for swine flu, which look to have been reasonably effective. But schools are a much smaller factor for Covid. Unlike the West, Southeast Asia at least fought the correct category of disease.

The flu is primarily spread through droplets – in practice, coughing and sneezing. Covid is mostly airborne; spread occurs through aerosols which are smaller than flu droplets. The difference really matters. Since Covid is airborne, outdoor spread is rare, as the circulation of air disperses the virus. And surface transmission is rare, too: our panicked sterilising of surfaces was probably a waste of time.

But the public health community, and the WHO in particular, rapidly converged upon the idea that Covid was spread by droplets and not aerosols. It took two years for the WHO to finally describe Covid as airborne. They loudly proclaimed in late March 2020 that it was a ‘FACT’ that Covid could not be spread by aerosols. The original suite of measures they recommended included physical distancing, staying inside, sterilising surfaces and not wearing masks. These are extremely different to what you would have recommended if you had known Covid was spread by aerosols: wearing masks, going outside, ventilating indoor spaces, and forgetting about surfaces. In fact, they’re almost opposite.

The WHO’s confusion arose, in part, from a truly bizarre source: they made a basic transcription error. I am completely serious. The WHO, and most textbooks, stated that five microns was the cutoff for an aerosol being large enough to be considered a ‘droplet’. In reality, much larger particles can act like aerosols, depending on the conditions. Somebody eventually traced back the five micron figure to a several decades old document from the CDC. The actual figure proposed for the cutoff of aerosols was one hundred microns, by the engineer William Firth Wells, which was misquoted as being twenty times smaller (you can read the exact account here). Thus was born the deadliest ‘leprechaun’ of all time.

Some employees at the WHO (correctly!) complained about how it was unreasonable for them to synthesise all the research and report on the scientific consensus where none existed yet. The organisation is much better at reporting the consensus after a topic has been studied for many years. Relying on a huge and slow-by-design international institution for up-to-date guidance was doomed from the beginning.

The 100/5 micron fiasco is an example of an illusory consensus. Anecdotally, Irish people were aware of public health advice from four bodies: NPHET, the WHO, the European CDC, and Anthony Fauci or other American sources. If they went on holidays, or had friends in other countries, they may have come into contact with guidance from elsewhere. If all these bodies are saying the same thing, it looks like there is a really strong consensus that the thing is true. But if all the advice is just parroting the WHO, then hearing multiple sources say the same thing shouldn’t actually make you more confident that it’s true.

Perhaps the craziest aspect of this story is that it’s not that unusual. Simkin and Roychowdhury estimate that academics only read 20% of the original papers they are citing. No, I have not read their paper, a fact which gave me a good chuckle. They tested this by seeing how often transcription errors are corrected; if a popular article misquotes an original source, will people cite the original result or the mistaken new one? The world is filled with falsehoods which started as simple errors but grew and grew until they took on a life of their own. Apparently, those falsehoods sometimes guide public health advice. The lunatics are running the asylum, my friends.

It would be funny if it weren’t so tragic. Instituions acted so cautiously to preserve their credibility that they completely undermined their credibility. Contrary to my expectations, my friends who trust public health advice the least are the ones who are the most informed about pandemic news and research.

A resistance to backtrack on public health advice created some seriously dodgy recommendations. Citizens Information (the national agency for information about public services) only started recommending that people wear medical or FFP2 rather than cloth masks in most contexts in February 2022. If people are going through the discomfort of wearing a face mask anyway, why tell them to wear the less effective type?

While I was writing this essay, I caught Covid, which made this personal. The Irish government recommends that you should self-isolate for seven days after a positive test. But is this because they genuinely think that’s how long you’re infectious for, or is it because they think, realistically, people will only isolate for five days, which is the more appropriate amount of time? After I develop symptoms, what is the best guess for how long I’ll be infectious for? This is one of the simplest questions you could possibly ask about the virus, and I still don’t have a clear answer to it.

4.4. There was little interest in cost-benefit analysis

Perhaps the biggest flaw of pandemic discourse was that there was very little weight given to, or even interest in, how different measures fared on a basic cost-benefit test. The benefit-cost ratio appears to have been relatively good for masks, banning large indoor gatherings, and bad for long school closures and restrictions on what people can do outdoors. But nobody knows for sure, because the whole thing is a mess of endogeneity, data quality issues, and cultural and ethnic differences. Data quality means that comparing European countries is challenging; you are better off comparing American states, and the verdict from that is decidedly mixed.

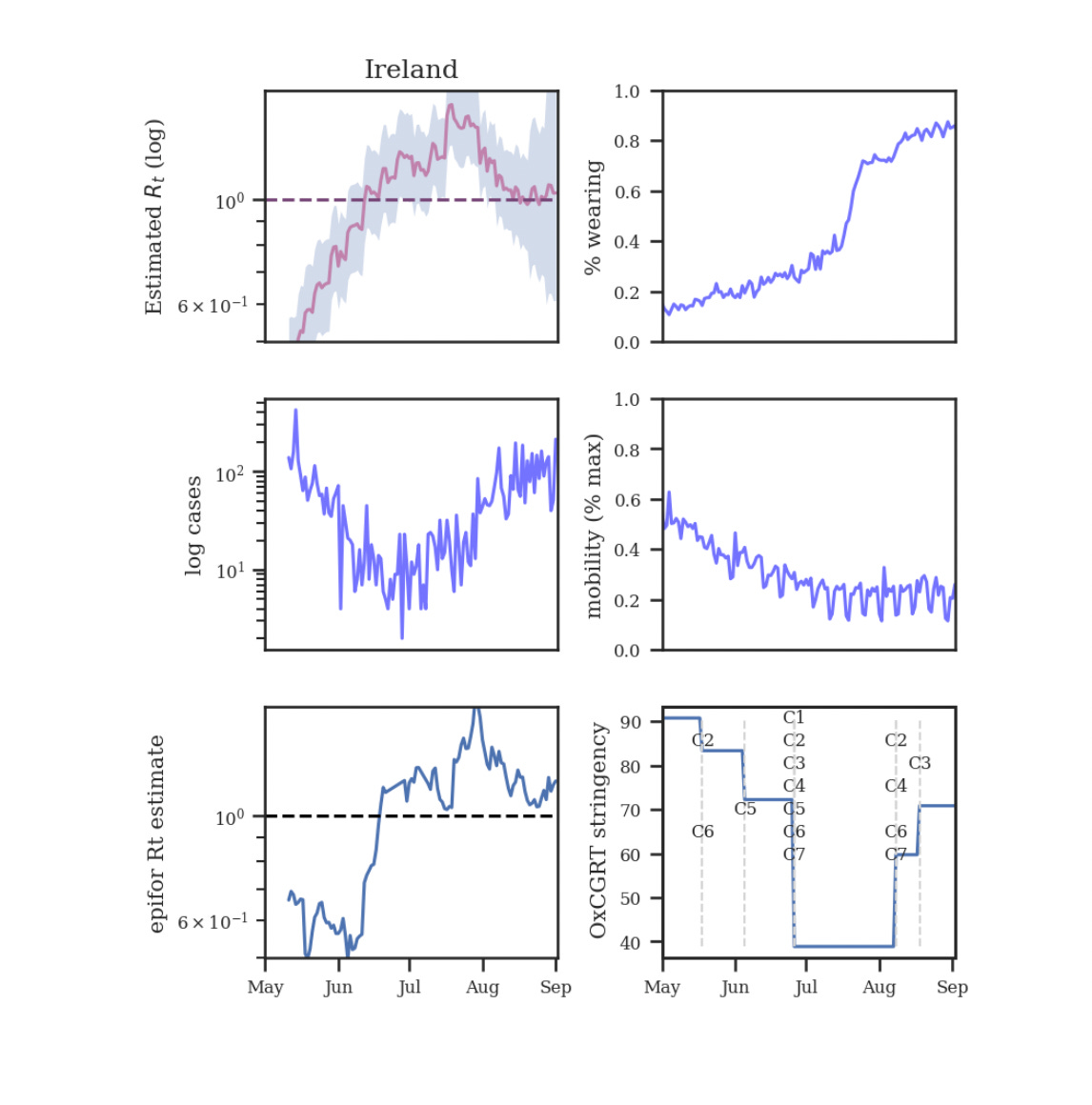

It’s actually even more complicated than this. A key assumption of basic epidemiological models is ‘homogenous mixing’: that an infected individual is equally likely to infect anyone in the population, or, sometimes, anyone within a certain age group in the population. This is obviously false, but the hope is that the errors will balance out or that it will be worth it to make the maths more tractable. Some heterodox thinkers, including Philippe Lemoine, argue that heterogenous mixing is key to understanding the pandemic. The reproduction number (i.e. the average number of people each infected person spreads the virus to) tracks mobility only very loosely. This is true even when a single variant is dominant. You can’t account for this if you think the population is mixing homogeneously. Population heterogeneity can cause us to substantially overstate the effectiveness of lockdowns. If the R number is predicted more by factors other than the degree of socialisation, it is necessarily predicted less by lockdowns. Like I said, tricky stuff.

Many Covid restrictions were pointless and arbitrary, and this was clear even at the time. In Scotland, where I currently live, I could go to the library, but I couldn’t take out any books (in case someone sneezed on the cover?). Gyms made you wear a mask when moving between equipment but not when using equipment. Many countries required masks outdoors long after it became clear that outdoor spread was vanishingly rare [Edit: Ourdoor transmission accounted for 0.1% of cases in Ireland]. Belgium and the Netherlands had rather oppressive curfews on when people could go out at night. Delhi required people to wear masks when they were alone in their cars until February this year. One of Ireland’s most arbitrary rules was that, over Christmas 2021, all hospitality venues had to close by 8pm, and weddings couldn’t go longer than midnight. 95% of adults were already vaccinated, and the people that were eligible but unvaccinated were fairly recalcitrant. Early closing times did dissuade some people from going to the pub at the margin, but the virus was so rampant that it was hardly a valuable margin to push on. What was the plan here, people?

Covid journalism, even from good outlets, missed the forest for the trees. It over-interpreted statistical noise, or missed key subtleties. Any sort of clarity on what went wrong (and right) takes time. Considering how it was all anyone talked about for two years, I’ve seen remarkably few attempts at actually explaining how different countries responded to Covid. Now that I’ve given my (tentative and uncertain!) best shot at that, I’ll discuss whether I think any actual procedures have been improved, and my recommendations.

4.5. Has anything been improved for next time?

I hate to say it, but probably not.

There are some big wins. Human challenge trials are more likely to be used. And we now have the miraculous mRNA technology. But, have any of the public health people – in Ireland or elsewhere – admitted they were wrong? Wrong about masks, wrong about asymptomatic transmission, and wrong about ventilation? No; they were completely rational given the information they had available at the time. Of course. Or, like Anthony Fauci, they knew the truth all along but lied to prevent panic.

The unwillingness of public-facing scientists to admit they were wrong betrays a disturbing incuriosity. These people trained for years because they love science, right? And they love science because they love discovering new things about the world, right? Yet I still saw disturbingly little interest in questions like: How does ventilation relate to Covid? Does UV light kill Covid? What type of air filters are best? Why is Covid seasonal?

Similarly, the media never had its mea culpa. The Irish Times never apologised for claiming there was “no evidence” for things that there was in fact lots of evidence for. Journalists admitting to being wrong about the pandemic is so rare that, when Dylan Matthews admitted to being wrong about pandemic-induced inflation, I almost spat out my coffee. The first step to recovery is admitting you have a problem.

Academia was almost as disappointing. Universities applied their normal mindset of non-urgency to an emergency. Covid research was rejected for being in the wrong font. Wealthy universities were glacially slow at approving grant applications for critical research, so much so that Patrick Collison had to step in to fill the funding gap. It’s quite the juxtaposition that, while Big Pharma was conducting some of the most important research of a generation, universities were producing a tsunami of low-quality papers. It was recently pointed out to me that there’s still no global dataset of Covid deaths by vaccination status. What we have is messy and cobbled together from estimates and national statistics. This has been one of the most important questions in science for the last two years. And yet the data still “sucks ass”, to quote one Covid researcher I spoke with. His words, not mine.

The overwhelming attitude toward pandemic preparedness is apathy. A $30 billion pandemic prevention bill looks like it will die for lack of support in the US Congress. Ireland doesn’t even have an analogous initiative. The only candidate Congressperson who was remotely serious about preventing pandemics just lost by a lot. Biosecurity projects are so strapped for cash that they are, once again, being funded by a tech billionaire.

As has been noted many times, Covid-19 was a pandemic on easy mode. It’s not hard to imagine a similar virus with ten times the lethality. What would we have done then? Would we still have rebuffed human challenge trials? Would we still have failed to increase hospital capacity? Would we still have rejected valuable public health measures out of phantom concerns about a “false sense of security”? Would we still have taken so long to approve vaccines and pharmaceuticals? It sends a shiver down my spine when I consider that the answers might be yes.

We are (maybe) seeing a repeat of the failures of the Covid response with monkeypox. This article describes how the US is making exactly the same mistakes with monkeypox as it did with Covid. The lessons learned by the quoted experts seem to amount to “this time we’ll do it right”. And the WHO, ever the master of prioritisation, is busy renaming ‘monkeypox’ to avoid accusations of racism.

The pandemic made you proud to be Irish, in the sense that vaccination and trust were high, and communities came together to an impressive degree. But can we be proud of any public institutions? No, not really.

4.6. My policy recommendations

It’s hard to give policy advice. The correct policy is dependent upon lots of information I don’t have. But, it would be too negative of me to write 12,000 words of diagnosis without any suggestions on how to improve things. So, here are thirteen recommendations I am reasonably confident can be taken ‘off the shelf’:

#1: Use human challenge trials!

The ethical arguments against them make no sense. Running a human challenge trial that is safe and free from litigation would be difficult; that is not in dispute. But, as David Deutsch likes to say, problems are soluble.

#2: Subsidise superforecasters and prediction markets

Read Superforecasting by Philip Tetlock (or see summaries here and here). Tetlock has conducted wide-ranging and indispensable research showing that experts are often not better at predicting outcomes than dart-throwing chimpanzees. However, you can train yourself to get better and become a ‘superforecaster’. Tetlock has discovered many techniques to improve your forecasts, including frequent probability updates and splitting up complex problems into smaller ones. All policy decisions rely on some forecast about what is likely to occur in the future. Yet we invest almost nothing in trying to improve these forecasts! In addition to superforecasters, prediction markets tend to generate accurate forecasts. A prediction market is when you bet on the outcome of an event, e.g. whether Joe Biden will win the 2024 presidential election. The ‘share’ will pay you out €1 if you are right, and €0 if you are wrong, and so the trading price of the share will reflect what the market thinks is the best probability estimate. Prediction markets force you to put skin in the game; one of the problems with experts is that they can use ‘vague verbiage’ to cover their posteriors in case they are wrong. Prediction markets are currently subject to a menagerie of onerous regulations. The world’s leading prediction market was founded in Dublin but disbanded (as I understand it) because the regulations were too costly and complicated to comply with. My proposal is to pay superforecasters to compete in forecasting tournaments about issues of national interest, including emerging infectious diseases. Also, to loosen the regulation on prediction markets, and run government-subsidised markets on information relevant to decision-making. A particularly useful tool is conditional prediction markets – betting on outcomes conditional upon something being true. For example, there may be a market on how Leaving Certificate results will change conditional upon a new educational policy passing, and a market about how they will change if it doesn’t. This both allows you to choose wiser policies, and to judge whether failures and overruns were predictable in advance. NPHET may tell us that the seriousness of Covid was not foreseeable in early March 2020. But if this had contradicted what their own prediction market had said, we wouldn’t tolerate such anatomy-covering.

#3: Stop using the phrase “no evidence”

Distribute a style guide to your public health people in which you tell them to stop saying “no evidence”, and start using numerical probability estimates wherever possible. “No evidence” is a weaselly phrase that helps you avoid actually forming an accurate worldview. One of the methodological difficulties of Tetlock’s work is that it’s really hard to get experts to make precise and verifiable predictions. They hate doing it. NPHET said there was “no evidence” that masks work. How sure were they? 10%? 50%? 90%? If you think that a word like “likely” does the trick, people don’t agree at all what is meant by phrases like “usually” and “likely”. I’m a big fan of betting and its ability to sharpen the mind. At what odds would Holohan have taken a bet about masking or testing? If he wouldn't accept a bet, how much can he really even believe his own advice? Is this a question that even crossed his mind?

[Edit: I think I was unclear here: it’s ok to say “no evidence” for things matching definition #3, i.e. that we know to be false. There’s no evidence that the vaccines

#4: All medicines approved by the FDA (America), MHRA (UK), PMDA (Japan), TGA (Australia), Medsafe (New Zealand), HPFB (Canada), or any other trusted regulator should be approved automatically in Ireland

The amount of duplication of work by approval bodies was incredible. America shot itself in the foot by not approving AstraZeneca. India was claiming that vaccine patents were oppressing them when they hadn’t even approved Pfizer. I assume crank cures sometimes get passed by the regulators in developing countries (although, they base their decisions on developed country regulators, so even this I’m not sure of). But we have no reason to believe drugs and vaccines approved in Canada or Japan aren’t also fine for Irish use. We’re all human.

#5: All doctors and nurses certified in any OECD country should also be certified in Ireland

And approvals from other countries with advanced medical systems should be swift. There is no crisis of there being “not enough doctors”. There is a crisis of enormous control over who can be a doctor and where they can work.

#6: Hospitals should be exempt from all local building codes

China can build a hospital faster than the local council in Ireland would reply to your email about planning permission. Irish people seem to think zoning is a fact of life, but the UK doesn’t have it. Put aside for the moment thoughts of the State leading the development of a new top-tier hospital. People are currently willing to pay enormous money for new private hospitals, but the government won’t let them. I’m not caricaturing the government as a monolith: there is a part of government which wants more hospitals, and allocates lots of money to it. And there is a part of government which enforces an arduous land-use system that makes building such hospitals almost impossible. There has been a profound failure to see any contradiction between these two roles. When the new as-yet-untitled children’s hospital in Dublin applied for planning permission, their application took six months and was rejected because the building didn’t look nice enough. There are several examples of people involved resigning out of frustration with the bureaucracy. From applying for planning permission to the first shovel hitting the ground took five years. From the plan being developed to construction took twenty-three years. There are almost never simple policy solutions, but this is one of them. Overnight you can solve much of this problem by abolishing zoning, planning permission, and all other forms of building restrictions for medical services. Will this mean all the buildings are ugly? Maybe, but there are other ways to solve this that don’t involve making it entirely unaffordable to provide essential medical services. Besides, unquestionably the most visually appealing hospital in Ireland is the Rotunda Hospital, which was built before building codes existed (gasp!).

#7: Diversify your information sources

On every new Covid development, I was made aware of it first through blogs and much later through public health advice. In this area, I would particularly recommend Marginal Revolution, Zvi Mowshowitz and Astral Codex Ten. I also found value in Twitter, including Nicholas Christakis and Marc Lipsitch. Twitter and blogs don't have to go through the same checks as traditional media outlets but, as I alluded to, the checks evidently aren’t very good.

#8: Red-team your pandemic plans

Ireland (I assume) has internal pandemic plans, and some of these might be very good. But the plan we went with had glaring errors, which implies that, probably, there were problems with the plans before the pandemic. It’s understandable that people made these mistakes at the time, under immense stress and time pressure. But the whole point of planning is to not get into circumstances where that sort of thing happens. I propose hiring researchers to scrutinise and criticise every line of the pandemic plans. When I write an essay, I send drafts to my friends, and they grill me and point out all the flaws in my argument. The essays are always better as a result. There is not currently a good equivalent of this in government. There is public comment, but that is different; I am talking about outside researchers working closely with the government and being rewarded for all the mistakes they find. In an ideal world, you would thank people for pointing out your mistakes. Let’s turn this up a notch and pay them.

#9: Be extremely hesitant to ban things that might help you

A pandemic is no time for arrogance. Various institutions repeatedly displayed such overwhelming confidence that their way was the right way that they banned all the other ways. The FDA’s first response to the pandemic was to ban testing, except through their proprietary test. The problem was, their test didn’t work. This is why Sierra Leone, one of the poorest countries in the world, was testing for Covid before the USA. Universities had already developed working tests, but the FDA wouldn’t allow them to be used. The West displayed much the same arrogance by banning vaccine markets. We collectively decided that it was worth it to let hundreds of thousands or millions of people die to uphold a notion of fairness. It’s hard to believe that private sector investment wouldn’t have sped up the vaccines: the justly celebrated Operation Warp Speed didn’t start spending serious money until August 2020. The European Union, and, by extension, Ireland, was much slower. I happily would have paid for the promise of a future vaccine in March 2020. It was as if we were tasked with curing cancer, and our first step was to defame and defraud the competing cancer charities.

#10: Allow “price gouging”

In a pandemic, the price of scarce inputs must rise. An increase in the price of masks will cause producers to ramp up their production, and for the masks that are sold to go to higher-value uses. You may recall several alcohol companies repurposed their machinery to produce hand sanitiser, but it seems they mostly did it as an act of charity or public relations. If you still have confidence that the government will adequately stockpile PPE and other critical supplies for next time after reading this series, I don’t know what more I can say. Producers are blocked from raising prices sometimes by legislation (as in some states in America) but more often by the possibility of extreme public backlash. Here’s a common pattern after natural disasters: producers raise prices to fund distributing their products to dangerous areas. There is a public backlash. Therefore producers don’t raise their prices next time, meaning they can’t afford to distribute food or other supplies to the effected area. Cue public outcry about why companies aren’t helping enough. While large pharmaceutical companies are unusually profitable, this is mostly because of patents. The profit margins on non-prescription products you can buy in a pharmacy are pretty darn slim. Perhaps the world would be better if companies produced what would be best for society out of the goodness of their hearts. But they don’t. We relied on the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer and the baker for our dinners, instead of their own self-interest, and we paid the cost.

#11: Have a diversity of vaccines, tests, and funding models

One of the under-discussed reasons why people don’t get vaccinated is that a certain segment of the population is absolutely terrified of needles. Nasal and oral vaccines are in development but there wasn’t much appetite to fund them after we got the effective needle-based vaccines. We should invest in a wide range of vaccines – much wider than what we actually think we’ll need. Just as we had too narrow a conception of what a vaccine could be, we had too narrow a conception of what a test could be. The existing regulatory framework was set up for highly accurate tests for diagnosis. There is a time and a place for these tests, and there is also a time and a place for cheap, rapid but less accurate tests. Similarly, the model for science funding is set up for large grants when there is time for a lengthy application and review process. There is a time and a place for these grants, and there is also a time and a place for small rapid grants that have a greater chance of failure. We should have both. Recipients of the Fast Grants program at the world’s wealthiest universities reported their Covid research was strapped for cash, because of the lengthy process of grant applications. Money money everywhere, but not a cent to spare.

#12: Spend early and often on candidate vaccines

Throw money at anything that looks remotely plausible. If none of the money goes to waste, you’re not taking enough risky enough bets. We should even have vaccine factories permanently ready to go. Being prepared is expensive, but not nearly as expensive as being unprepared.

#13: Celebrate heroes

The vaccines proved that our civilisation is still capable of greatness on the scale of the Apollo program. Yet, can the average person on the street even name a single individual that designed and built them? This New York Times article about Katalin Karikó, pioneer of mRNA technology, is unbelievably depressing. She spent decades on the fringes of academia struggling to get research funding or recognition. After Salk developed the polio vaccine, people partied in the streets. Today, we get endless screeds about how “tech can’t save us” and Big Pharma is “profiting from pain”. I’m not saying there is no merit to these complaints. But a word of advice: before you criticise, go to where people are doing truly extraordinary things, and observe. Listen, for ye have much to learn.

Sam Enright is executive editor of the Fitzwilliam.

The frase "the science" should be banned. It presents science as static and unchanging.

People will often cite how economic forecastors are "irrationally" certain about their forecasts. Gerd Gigerenzer points out that overstating forecast accuracy is actually rational. If you want to be successful in the forecasting game you have to pretend you can actually do it. This is a plague in science and medical communication. They think it hurts their credibility to honestly describe the uncertainty. Thus it's masks don't work to masks always work and never, the empirical evidence for masks working is weak, but on balance suggests it could be beneficial in many circumstances.

When they change policy they'll say "the science changed, so we changed our approach." They imply that the approach was correct before, but a new approach is needed now, but what they are actually saying, without realizing it, is that they were wrong before and now we have scientific proof of it.