Turning Back the Economic Clock

The real danger embodied by Bram Stoker's Dracula

In Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula, published in 1897, Count Dracula is not only a bloodthirsty killer, but an existential threat to modernism and progress. Contemporary readers of the novel could not help but shiver when Dracula landed at Whitby, England to turn victims into vampires and to turn the economic clock backwards, bringing superstition and an antiquated mentality to Great Britain.

To the economic historian, the biggest danger of Dracula is his potential disruption of civil timekeeping systems, which would undermine railway safety, mail, contracts, and modern commerce generally. Great Britain’s economic prosperity was becoming increasingly dependent on international standards, such as the global adoption of Greenwich Mean Time and the Universal Day. Dracula, whose powers are governed by the sun and the moon rather than clocks and calendars, threatens to destabilise social coordination. If he gained power, he would bring down the economy.

Though Ireland does not play a central role in Dracula, Stoker’s emphasis on time standards and timekeeping in the novel is a critique of Ireland’s policy of being out of step with Greenwich Mean Time. The persistent 25-minute mismatch between mainland Britain and the island of Ireland was sucking the lifeblood out of both economies.

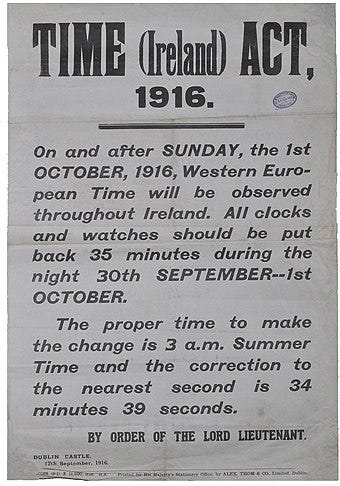

Bram Stoker was born in Dublin on November 8, 1847, the third of seven children born to civil servant Abraham Stoker and Charlotte Mathilda Blake Thornley. Their eldest son, Sir Thornley Stoker, was a noted surgeon and President of the Royal Academy of Medicine in Ireland. The less academically inclined Bram Stoker, after graduating with a B.A. and M.A. from Trinity College Dublin, was able to secure a day job as a civil servant, with the help of his father. This job allowed him to go to the theatre at night, writing reviews for the Evening Mail. Most biographers skip over Stoker’s time as a court clerk but the experience is key to understanding the deep knowledge he had of time policy and its attendant frustrations. A pressing concern after the establishment of Greenwich Mean Time was settling legal time in local jurisdictions. Should courts use GMT or local time? The matter was partially settled in 1858, when legal time was set as a matter of local time, which differed from town to town. Matters were somewhat simplified in 1880, when Dublin Mean Time (kept at Dunsink Observatory) was set as the legal time for all of Ireland at 25 minutes and 21 seconds behind Greenwich Mean Time. This was fine for Ireland but perpetually confusing for anyone venturing outside its borders. Dublin Mean Time remained a growing irritation for travellers, the telegraph system, and the railroads. Still, it lasted until after the 1916 Easter Rising, when the Time Act aligned Irish Time with Greenwich Mean Time, despite political opposition.

Dracula emerges at a moment when Stoker had been travelling around Great Britain widely, living in London (since 1878) and Aberdeenshire, Scotland, as well as journeying around the world. He increasingly saw that an international agreement on time was essential for economic progress.

Dracula and global timekeeping

How does this history help us see Dracula as a novel concerned with global timekeeping? Stoker’s tale opens with a young lawyer, Jonathan Harker, travelling to Transylvania to help the mysterious Count Dracula purchase a home in London. “I long to go through the crowded streets of your mighty London, to be in the midst of the whirl and rush of humanity, to share its life, its change, its death, and all that makes it what it is,” Dracula tells him. The Count is fascinated by modernity; he has been reading George Bradshaw’s railroad timetables, presumably to help him understand how to navigate a modern city. But why? It is not enough that Dracula turns victims into vampires, as the movies tend to emphasise. He also puts them in a mental fog so that they cannot participate in economic life. “[H]e cannot think of time yet,” Harker’s wife Mina laments, nursing him to health after a close escape from the vampire’s lair; “at first he mixes up not only the month, but the year.” Under Dracula’s spell, humans forget the time, becoming listless and unproductive. Dracula’s objective is not only literally to “fatten on the blood of the living,” but also more broadly to suck the lifeblood of a thriving commercial economy.

Readers who have only seen Dracula at the movies may be surprised at the time Stoker spends detailing the vampire’s interest in supply chains, citing books and directories on customs, law, shipping, and transportation routes. Stoker was well versed in this kind of reading material; his first book, Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland, (1879) was an attempt to bring order and method to the process of administering criminal courts.

Dracula’s plans for infecting Britain are told in a series of dated journal entries, letters, captains’ logs, newspaper articles, and other records, all in strict chronological order. Dracula is one of the first novels of modern paperwork. To read it is to understand the most up-to-date communication technologies of the day. If Stoker were writing his novel in 2022, he might have used a compilation of texts, blog posts, Tweets, and TikToks.

Standard time concepts like seconds, minutes, hours, clocks, and calendars are now so widely accepted that they seem inevitable. Modern readers take for granted a global agreement on time and timezones. But global agreement was new and not always reliable in Stoker’s day, as he discussed in The Duties of Clerks: “Experience has shown me that with several hundred men performing daily a multitude of acts of greater or lesser importance, a certain uniformity of method is necessary.” What is modernity without order and method? Indeed, order and method are what finally kill Count Dracula.

Stoker requires his readers to use their basic understanding of date and time-keeping systems, particularly Standard Time and the Gregorian calendar, to follow the logical sequence of events in Dracula. As I explained in Killing Time: Dracula and Social Discoordination, when Stoker was writing Dracula, the notion of a standard time was still being argued in Ireland and Britain, half a century after the establishment of Greenwich Mean Time. The old ways were hard to shake off. For most of human history, people kept local time, marked by sundials and tolled by church bells. For some cultures, the new day might begin at sunset; for others, dawn; for others, midnight. After the development of the mechanical clock in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, clock towers were introduced in larger cities around Europe to standardise the workday and regulate municipal courts, assemblies, and markets. Hourglasses soon joined smaller mechanical clocks in schools and homes. But local times widely diverged and there was often only a rough agreement about time and date. Minute hands only became widely used in the eighteenth century.

The expansion of postal routes and railway lines necessitated national (and soon international) time standards and timetables. Railway companies, recognising the need for a standard time, adopted an industry standard, Railway Time, in 1840. Greenwich Mean Time replaced Railway Time for British railways in 1847. In 1859, Big Ben was installed in London, tolling Greenwich time. In 1884, the International Meridian Conference in Washington D.C. recommended that all countries adopt Universal Time (with Greenwich as the prime meridian) and the Universal 24-hour day, to begin at midnight. Of particular relevance to Dracula, two of the delegations voting ‘No’ to this resolution were Austria-Hungary and Turkey, on either side of Transylvania. Both wanted the day to start at noon.

By drawing his readers into agreeing with the universal authority of time and date systems, Stoker was turning them into proponents of modern timekeeping, and future advocates for fixing Ireland’s persistent time obstinacy.

Standards are essential to coordinate behaviour. But across Europe, even the calendar was still not universally agreed upon in Bram Stoker’s lifetime. The Gregorian calendar had been in use by Roman Catholic countries in Western Europe since the sixteenth century, while the Eastern Orthodox regions of Eastern Europe, including the regions surrounding Transylvania, still followed the Julian calendar. Instituted by Julius Caesar in 45 BCE, the Julian calendar, adopted as the basis of the official Church calendar at the Council of Nicea in 325, had slowly drifted away from its Biblical, seasonal, and astronomical footings. In 725, the English monk Bede observed in his treatise “The Reckoning of Time” (De temporum ratione) that the vernal equinox (a crucial variable for fixing the date of Easter) was becoming irreconcilable with the calendar. By the fifteenth century, the vernal equinox had drifted eleven days, falling on March 10 instead of March 21. In 1583, Pope Gregory XIII authorised a new calendar that would set the vernal equinox to March 21. The Gregorian calendar was adopted almost immediately in Italy, Portugal, Spain, Poland, Luxembourg, France, Belgium, Austria, Catholic Germany, Catholic Switzerland, and Catholic Holland. Hungary followed in 1587.

The adoption of the Gregorian calendar by Protestant nations took more than a century. Elizabethan England, newly split from the Catholic Church, was initially wary; Protestant Germany rejected it out of hand. A serious concern about the adoption of the reformed calendar was the loss of ten days (which would grow to eleven by 1700, when Germany, Denmark, and Switzerland made the transition). Merchants, tradesmen, astronomers, and scientists in England repeatedly advocated for unification of the calendar with the Continent, but internal political and theological disputes delayed change. Gradually, economic and scientific interests eclipsed theological concerns. Finally, in 1752, Great Britain and her colonies (including America) adopted the “new style” calendar with a mandate that Wednesday, September 2 would be followed by Thursday, September 14, and that the new year would begin on January 1.1

The history of time coordination was well known to Stoker. He knew well that in 1897, countries and regions following the Eastern Orthodox Church, including Romania, were still fighting over the calendar (and would continue to do so until after WWI). Transylvania, on the border of Romania and Hungary, had been caught between two competing calendars for centuries.

Time and date confusion

Stoker’s novel is a study in the contrast between Western Europe’s expectations for promptness and efficiency against the East. Jonathan Harker complains on his trip to Transylvania, “After rushing to the station at 7:30 I had to sit in the carriage for more than an hour before we began to move. It seems to me that the further East you go the more unpunctual are the trains.” Indeed, Transylvania was left out of British time protocols and was still suffering date confusion because of overlapping use of the Julian and Gregorian calendars.

Discrepancies about days may have been behind popular belief in the undead in Eastern Europe. Consider that a person who died on April 1 and was buried on April 3 under the Julian calendar could be remembered strolling about by a Gregorian calendar follower on, say, April 7 (March 28 under the Julian calendar). Scholars last century began to put together what Stoker knew: that reports of vampires and dead men walking from their graves were the most common in border regions, where both the Julian and Gregorian calendars were in use.

In the working drafts of his novel, Stoker notes the “old style” dates in his outline in two places: Thursday, March 16 (“dated 4 March old style”), and Thursday, March 30 (“18 old style”). In a way, Dracula is indifferent to humans’ disputes about calendars and timekeeping; he is immortal, after all. Yet, Dracula appreciates the utility of shipping and railway schedules and uses these networks to transport local soil (which he must sleep in to survive) to London. Dracula also knows how to create time and date uncertainty in others for his own advantage. Under Dracula’s influence, Jonathan forgets to wind his watch. Dracula compels him to post-date letters, puzzling his correspondents before he sets sail for England, leaving the lawyer imprisoned in the castle. Dracula exploits modern time conventions to manipulate and control human beings. The captain of the Russian ship Demeter, transporting Dracula and boxes of Transylvanian soil to England, falters in timekeeping. Dracula brings the fog of time confusion with him to England.

Dracula fully understands that British compliance with standards and laws will ensure that his legal and commercial transactions will be carried out. Even with the captain dead, and Demeter crashed into gravel in the port of Whitby, Dracula’s cargo is safe: the local officials of the Board of Trade are “most exacting in seeing that every compliance has been made with existing regulations.” The Coast Guard, first to board, cannot claim rights of salvage from what seems to be a derelict craft. The boxes of soil are duly sent to a Whitby solicitor named on the manifest, who takes possession and forwards the crates to London.

Dracula’s concern with time coordination is also evident in the vampire’s arrival in Whitby, the site of England’s first calendar controversy. Stoker visited the town often and borrowed from the local library William Wilkinson’s Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia. He knew well the history of the Synod of Whitby, which ruled in 664 CE that the date of Easter would be calculated with the Roman (Julian) system, and not the Celtic system used on the island of Iona.2 Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731) praises the bishop Wilfrid, who advocated a coordinated worldwide celebration of the Resurrection:

[As is] practiced in Africa, Asia, Egypt, Greece, and all the world, wherever the church of Christ is spread abroad, through several nations and tongues, at one and the same time; except only these and their accomplices in obstinacy, I mean the Picts and the Britons, who foolishly, in these two remote islands of the world, and only in part even of them, oppose all the rest of the universe.3

Bede suggests that synchronising the British celebration of Easter with Rome and the world had unified and coordinated the nation, preventing the tribal bloodshed of earlier eras. Like systems of language, calendars and timekeeping standards – both civil and religious – bind communities together.

Dracula’s arrival signals the loosening of temporal coordination. Stoker’s careful time notations in Dracula indicate whether humans or vampires are in control. When the time is given in natural terms (sunrise, sunset, moonrise, evening), Dracula is growing in power and humans are in danger. When a person looks at his or her watch, notes the hourly time, notes the time of trains or the tolling of bells, or coordinates with others, Dracula’s power is waning.

The power of coordination

Ultimately, Dracula’s natural time constraints are his undoing. His power wanes with the rising of the sun and he only has real power after sunset. Jonathan Harker and vampire expert Van Helsing study his limitations to best him. Harker’s friends rally by turning individual memories into calendar events; journals and documents are put into chronological order, enabling a clear assessment of Dracula’s activities. Their growing power is indicated by time specificity, such as Mina’s note to Van Helsing:

I have this moment, whilst writing, had a wire from Jonathan, saying that he leaves by the 6:25 tonight from Launceston and will be here at 10:18, so that I shall have no fear tonight. Will you, therefore, instead of lunching with us, please come to breakfast at eight o'clock, if this be not too early for you? You can get away, if you are in a hurry, by the 10:30 train, which will bring you to Paddington by 2:35.

The team begins meeting regularly. The paper trail of the boxes of soil is followed. All but one is found and purified. Dracula flees back to Transylvania by sea and land, pursued by Van Helsing and his team, as John Seward’s diary details:

“When does the next train start for Galatz?” [Van Helsing]

“At 6:30 tomorrow morning!” [Mina]

“How on earth do you know?” [Quincey Morris]

“You forget….that I am the train fiend” [Mina]

“Wonderful woman…Now let us organize.” [Van Helsing] “Arthur, go to the train and get the tickets….Jonathan, go to the agent of the ship and get from him letters to the agent in Galatz, with authority to search the ship just as it was here. Morris Quincey, you see the Vice-Consul, and get his aid with the fellow in Galatz and all he can do to make our way smooth, so that no times be lost when over the Danube. John will stay with Madam Mina and me, and we shall consult….it will not matter when the sun set.”

Coordination pays off: knowing about the train timetables, the transportation network, and the vampire’s limitations, the heroes are able to overtake Dracula just in time. Lying powerless in his coffin, he is stabbed in the heart, outside his castle, at sunset. Stoker’s point is made. The danger Dracula poses is the danger of market destabilisation and social dissolution – a transformation of British modernity into Transylvanian backwardness.

For Irish readers, Stoker was making a well-understood point: it was crucial to get on board with Greenwich Mean Time. He was not alone in seeing Irish time confusion as a source of literary inspiration. In James Joyce’s Ulysses, famously set in Dublin on June 16, 1904, Leopold Boom, in Chapter 8, “Laestrygonians,” contemplates time passing and the discrepancy between London time and Dublin time: “Now that I come to think of it that ball falls at Greenwich time. It’s the clock is worked by an electric wire from Dunsink.” Bloom has to spend time calculating the difference between 1:00, when the ball drops, and the local time kept by clocks. Perhaps literature was the only positive effect Stoker saw as emerging from temporal confusion and frustration.

Dracula’s planned enterprise might be read as a startup that never got off the ground. Expansion of Dracula’s domain would require a certain kind of corporate organization – establishing a network of associates and brokers – of which he seems incapable. Even the vampires he creates are not partners in scaling up the endeavour. Dracula’s primary marginal need is blood, not market share; he exploits the expertise of professionals and the labour of shippers and hauliers but does not create a business plan.

Dracula is not rational but instinctual, as Stoker’s working notes to the novel make clear:

Goes through life entirely by instinct;

Must cross running water at the exact flood or slack of the tide;

Has an influence over rats and over the animals in the zoological gardens;

Absolutely despises death and the dead;

Loves creating evil thoughts in others and banishing good ones—thus destroying their will;

Can see in the dark and can even get through the thickest of London fogs by instinct;

Is insensible to the beauties of music;

Has white teeth and the magic power of making himself large or small;

Must be carried, led, helped, or in some way welcomed over the threshold;

Is enormously strong, even though he never—apparently—eats or drinks;

Has an ambivalent attitude towards the icons of religion: he can be moved only by relics older than his own real date or century (that is, when he actually lived)— more recent relics leave him unmoved;

Always uses for money his stores of old gold;

Impossible to photograph, casts no reflection, gives no shadow.

Most of these characteristics are about Dracula’s hardwiring. In the world of Stoker’s novel, vampiric expansion is impossible. Accumulation of anything, including power and gold, is limited by Dracula’s inability to put together a reliable management team.

Global timekeeping is universal, official, and mechanical. Nineteenth-century opponents of Standard Time argued for the importance of local control and the health benefits of “natural” cycles and against globalised “machine time.” The joke about anti-Greenwich sentiment in Ireland was that locals simply thought the sun rose half an hour later in Dublin than it did in Liverpool.

Dracula is a rich and layered book that has attracted a great deal of scholarship. The inclusion of many themes relating to economics and social organisation in the novel was clear to its original readers, and was commented upon at the time. The threat that Dracula represents has variously been interpreted as feminism, homosexuality, colonialism, and even capitalism. It was not hard to convince Tyler Cowen of Bram Stoker’s interest in progress. Stoker’s fascination with timekeeping is part of his progress mindset. The creation of internationally agreed-upon standards for weights, measures, and time is absolutely critical for modern civilisation, and it was not a foregone conclusion. Dracula warned Ireland – and the rest of the world – of the mischief that arises from disjunctions in time.

Hollis Robbins is the Dean of Humanities at the University of Utah. Her research focuses on African-American literature. You can follow her on Twitter here.

Isaac Newton earlier advocated a plan that would ease financial disruption, proposing directives “for performance of all covenants duties and services and payment of interest, rents, salaries, pensions, wages, and all other debts and dues whatsoever with an abatement…proportional unto eleven days” (Poole, 131). Newton’s advice was not followed by those in charge of implementing the new calendar; rather, a gradual system was used. Still, official tables of abatements were published in the press and in almanacks so that landlords, tenants, and tradesmen could muddle through.

For most Catholics and Protestants, Easter is observed on the first Sunday following the full moon that occurs on or following the spring equinox (March 21). Eastern Orthodox followers observe Easter according to the date of the Passover festival. There is no controversy when the moon rises on the fourteenth day of the month after the spring equinox when the fifteenth day is a Sunday. But because the cycles of the sun and the moon are not easily aligned with the cycle of the days of the week, trouble arises when the fourteenth falls on any other day but a Saturday. The dispute is longstanding. Saint John celebrated Easter on the fifteenth of the month regardless of the day of the week, while Saint Peter, according to Bede, “tarried for the Sunday.”

Bede, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Trans. Bertram Colgrave. McClure, Judith and Collins, Roger, ed. (Oxford University Press, 2008): 155.

What a wonderful, delightful, informative post. Outstanding and really interesting. Remarkable how coordination problems caused by temporal asynchrony arise, and how they are resolved.

And despite the Easter Rising, no one wished to go back to DMT... revolutionaries must be practical, if they are not to fail...

I love this post. But - and it’s a big but - when we did our Curiously Specific Book Club podcast on Dracula we discovered that the train times Stoker uses in the book are mostly entirely incorrect! Mina In particular is absolutely all over the place.