We Were Promised Flying Cars…

A review of ‘The Rise and Fall of American Growth’

If something can’t go on forever, it won’t. Or at least, this is what Robert Gordon argues in The Rise and Fall of American Growth. He claims that the astonishing economic and technological growth of America in the 20th century is never to be repeated. Rich countries at the technological frontier have picked the low-hanging fruit. All the obvious ideas for useful inventions have already been taken.

American economic growth first began to pick up around 1770. Growth was pretty good from 1870 to 1920, then breathtaking from 1920 to 1970 (minus a huge dip from the Great Depression), and sluggish ever since. This growth slowdown has come to be known as ‘The Great Stagnation’, a term popularised by Tyler Cowen.

The subjective quality of life in frontier economies was completely transformed from 1920 to 1970. In that fifty-year window, most American households gained access to flush toilets, electricity, and cars. If you ignore phones and screens (admittedly a huge omission), life has changed comparatively little since – hence Peter Thiel’s now-famous adage that “We were promised flying cars, and instead we got 140 characters.”

If you just look at a graph of GDP, the Great Stagnation is by no means apparent. The growth rate of American GDP per capita has been suspiciously stable since the nation’s founding:

This is a log plot, which makes exponential relationships look linear, and smoothes out fluctuations. If you look at the linear plot, and extrapolate the pre-1970 trend, it’s more apparent though still not totally obvious that there was a big growth slowdown.

Note that what we’re talking about here are growth rates, not growth in an absolute sense. If a quantity is increasing by the same amount each year, then the rate of growth is falling. The Great Stagnation does not refer to a plateauing of wealth (no such phenomenon has occurred) or technology, but a substantial drop in the rate of growth.

The Great Stagnation could more accurately be called the Great Reversion to the Historical Norm. The postwar period had an unusual confluence of factors that led to spectacular growth for America and a number of other countries.

The key metric in Gordon’s book is total factor productivity (TFP). It’s commonly considered to be a measure of technology, or how efficiently labour and capital can be deployed in the economy. Probably the single best sentence to summarise this book is this: TFP grew at a third the rate after 1970 as it did from 1920 to 1970.1

What about other countries?

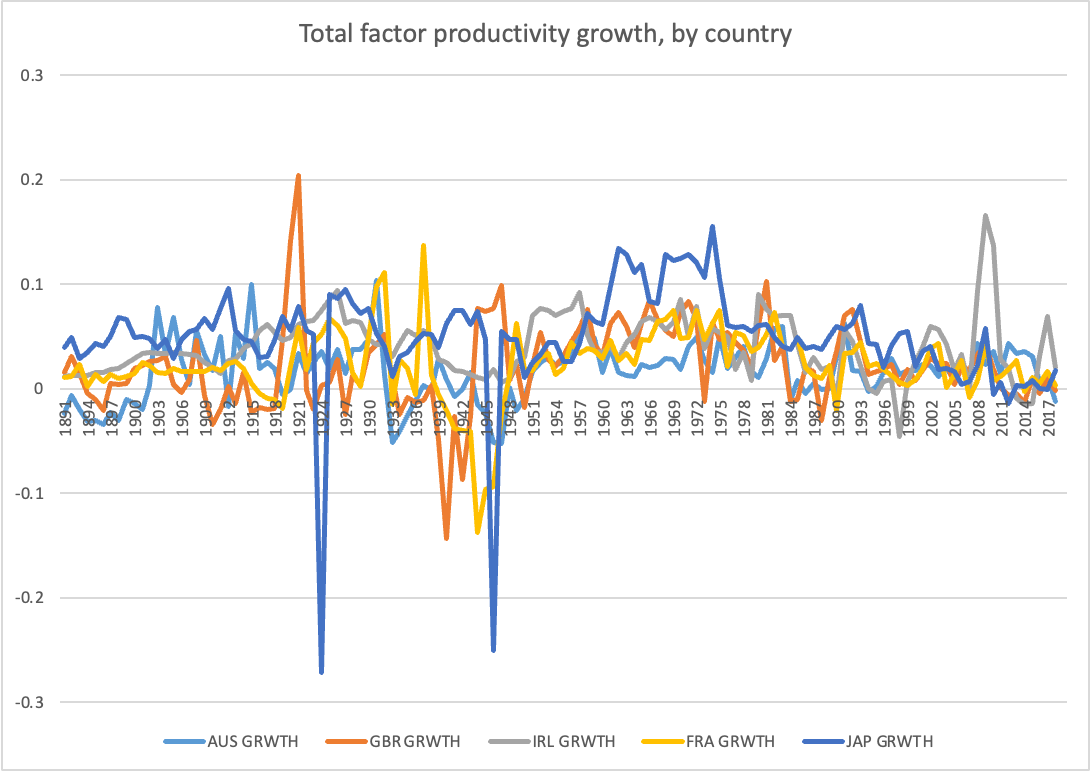

Gordon’s book is almost frustratingly America-centric, with only the occasional allusion that something similar is true of other rich countries. Did other countries have a Great Stagnation too? We should be able to answer this with the Long Term Productivity Database, which has data on total factor productivity going back to 1890, and from which I cobbled together this graph:

Most rich countries show TFP increasing roughly linearly since the 70s. Ireland is a big exception; TFP goes to the moon in the 2000s. I’m not sure whether to trust this due to Ireland’s infamously misleading economic indicators.

If TFP is going up and to the right, then what’s the problem? At least by this measure, technological improvement has not been slowing in rich countries in absolute terms, but it has been slowing proportionately.

At this point, I get confused about what the stagnationists are even arguing. Should I expect technology to improve by a similar amount each year, or should I expect it to improve by a similar percentage? One recent paper argues that linear TFP growth is in fact the more natural assumption. But an optimist would expect exponential growth: innovations naturally build on one another. If technology is improving by a constant amount per year, then innovation per person, or per resource invested, is likely to be shrinking massively.

When you look at TFP growth instead, it looks like this:

The Great Stagnation is the gentle slope downward from 1971 to today. You can see that in the countries featured, as of 2019, TFP is barely increasing at all.2

Ideas are getting harder to find

Here is what I think is going on: there are two forces pushing in opposite directions. Ideas are getting harder to find, and there are more people and resources going into research and development.3 That is both because of population growth, and because an increasing fraction of the population are contributing to new technologies. Sometimes, the two forces cancel each other out to a remarkably constant degree.

Think about how much easier it used to be to discover things. Robert Hooke could make foundational discoveries just by pointing a microscope at things no one had thought to point a microscope at before. Many discoveries were made by gentleman scientists in their spare time. Anecdotally, even in the 20th century, there were many more serendipitous discoveries than today. Penzias and Wilson received the Nobel Prize for discovering the cosmic microwave background after they picked up interference during an unrelated experiment (they famously thought it was bird poo). Paul Dirac once described the early 20th century as the time when even second-rate physicists could do first-rate work.

The extent of background knowledge required to make a scientific contribution has never been higher. It can take years of intensive training to even understand what the state of the art in a field is, to a much greater extent than in the past. Scientists often don’t even understand adjacent and extremely similar subfields. Our capacity to learn and communicate has improved too, but one has to imagine that there are limits on the human attention span. This is a hand-wavy argument to be sure, but, on the whole, it does seem that important discoveries have been getting harder to make.

Consider a model where economic growth is driven by a higher population (i.e. more labour), more capital, and higher TFP. Because of depreciation, there is an optimal level of capital; If you had too much of it, you would spend so much on the upkeep that your economy would actually shrink. Once countries reach this optimal capital stock, their per-person growth will be driven by ideas – finding better ways to put their labour to use.4 If ideas are getting harder to find, you can compensate for a while by dedicating a greater fraction of the workforce to idea-production, but there are obviously limits to this. In this toy model, economic growth will eventually come to an end.

There is an interesting section in What We Owe the Future where Will MacAskill extrapolates out such a model, which, combined with estimates for when world population will peak, finds that economic growth will only go on for another century or two in frontier economies.5 To be clear, he’s not saying this will happen, but that it’s the continuation of the observed pattern.

Gordon, as mentioned, is generally of the view that ideas are getting harder to find. If high economic growth necessarily runs out of juice, that would be sad and a shame, but it doesn’t indicate any foul play or bad policy decisions.

Scott Alexander makes an interesting argument that it’s almost inconceivable that some version of the stagnation argument isn’t true. Maintaining trends like Moore’s law has required an exponential increase in the financial and human capital dedicated to creating chips – if for no other reason than arithmetic, this can’t go on forever. He writes that “constant growth rates in response to exponentially increasing inputs is the null hypothesis.”

In some areas like crop yields and transistors, researchers appear to be almost twenty-five times less productive than they used to be.6 Perhaps there is a disastrous regulation killing progress in the soybean industry. Perhaps the upstart soybean farmers don’t have the right cultural values, or Big Soy is conspiring to sabotage the more efficient farming methods. All of those factors combined are unlikely to explain a 25x slowdown. There is room for all your pet theories to be correct, and more.

(Maybe there is only a small number of super-geniuses who drive forward progress in most areas, so adding a legion of Ph.D. drones doesn’t really help. On the other hand, we have presumably gotten better at talent identification, and broadened who can contribute to idea-production.)

The question, then, is how much of what rich countries have experienced is this inevitable stagnation built into the structure of the universe, and how much of it is historically contingent.

This is what stagnation-sceptics, like David Deutsch, tend to miss. He attributes declining researcher productivity to a growth in university bureaucracy, and denies the conceptual possibility of ideas getting harder to find. I’ll cede, for the sake of argument, that the inefficiencies of modern universities are making academics half as productive as they otherwise would be. I’ll even assume that universities are making them five times less efficient! I don’t think even this is enough to account for how much researcher productivity has declined since the days of Victorian gentlemen making earth-shattering discoveries in their spare time.

There are many technologies, like the internet, which researchers should be able to use to make themselves more productive. If ideas were not getting harder to find, you would need the distractions of email, meetings, and persnickety journal editors to make academics orders of magnitude worse at their jobs, enough to more than cancel out the effect of the improved technology. And this is just not plausible to me.

Finding new s-curves

The lifecycle of an idea is this: slow progress at first, as people begin understanding that it is important, then rapid progress, followed by stagnation. This is called an ‘s-curve’.

Certain areas, like AI, are currently advancing rapidly. This can only happen because we have expanded to new s-curves. While the obvious ideas for how to increase soybean yields have been taken, AI is sufficiently new that not all the low-hanging fruit has been picked. Knowledge can expand both in depth (up the s-curve) and breadth (new s-curves).

There are reasons to think that we can’t continue economic growth forever by finding new s-curves. Humans have certain preferences, and these are only malleable to a certain degree. If farmers switched from soybeans to producing futuristic edible slime, then we might see rapid progress (but I will not eat the slime). Also, if you extrapolate the current growth rate of economic growth for a few thousand more years, you conclude that there will be multiple world economies per atom. For economic growth to persist for more than a few hundred or thousand years requires some very futuristic changes, like artificial general intelligence or emulated minds. I’m not taking a stance on whether or not that will happen, but I struggle to see a future with persistent economic growth that is remotely recognisable.

Other possible explanations for stagnation

1. Bretton Woods and high oil prices

The exact start date of the growth slowdown appears to coincide with Nixon taking the US off the Bretton Woods system in 1971, and almost coincides with the oil shock in 1973. However, those are just reasons it was 1973 and not ’74 or ‘75; neither is important enough to get more than a passing mention in Gordon’s book. The start date of 1971 is suspiciously common for a number of social and economic trends – for more, see the website WTF Happened in 1971?

Oil prices have not been uniformly high since the 70s. Prices came down and by the late 90s were in line with the historical norm. Also, oil is cheaper than orange juice; I would be surprised if oil prices were a significant hurdle to innovation.

2. Cost disease

Consider a simplified economy in which people can either work in a factory, or as a musician in a string quartet. In the last two hundred years, new technology has enormously increased the productivity of the factory workers. But it takes the same number of people the same amount of time to perform a Beethoven string quartet as it did when they were first performed; their “productivity” has not improved at all. As the factory workers get more productive, you also need to pay higher wages to the musicians, to prevent them from jumping ship and working at the factory.

This is how William Baumol first introduced the concept of ‘cost disease’. Lower productivity-growth sectors will rise in cost relative to higher-productivity growth ones.

The relevance here is that the areas that drive innovation may be particularly hard-hit by Baumol’s disease. Academia in general is adept at providing the same or worse product as it used to for vastly more money (government and otherwise). The construction industry also seems to have significant cost disease – part of why costs for large infrastructure projects so often seem to be spiraling out of control.

Sometimes I think about whether there was a critical window after World War II in which countries were rich enough to build important civic infrastructure, but not so rich that doing so became infeasible (due to Baumol’s disease and other structural changes). If your country missed this window, then you have my sympathies. Ireland is in many ways a fabulously wealthy place, but I have my doubts whether Dublin could build a metro system if God himself donated his personal fortune.

Baumol’s disease is also relevant because of how it affects welfare. My low-confidence guess is that cost disease is particularly pronounced in areas that are most important for leading a fulfilled life, like education and healthcare. The cost declines in some sectors have been truly extraordinary, but have disproportionately been in things you didn’t really need anyway.

(There is a snag in this story, which is that the wages of professions like doctors and teachers have in many cases been falling in relative terms. So it seems that the Baumol effect must be mediated by a greater number of employees being in the lower-productivity sectors, rather than higher wages per se. For more, see Helland and Tabarrok’s Why Are the Prices so Damn High?)

3. Excessive regulation

Many people subscribe to the view that the Great Stagnation was not inevitable, and is due to an accumulation of harmful regulations and bad cultural traits. A prominent example of this is J. Storrs Hall’s book Where’s My Flying Car?

There are many alleged examples of the government strangling progress in certain areas, which would certainly slow growth. For example, zoning and planning permission make it extremely difficult to build new houses in economically productive areas. It has also become progressively harder to get new drugs and medical devices approved. A standard estimate of the cost of bringing a new drug to market is more than $2 billion (Because Europe has price controls, America is still the undisputed leader in new drug development). It’s pretty hard to imagine a scenario in which the enormous cost of getting approval isn’t a hurdle to pharmaceutical innovation. And as was previously discussed in the Fitzwilliam, nuclear power has been nigh on regulated out of existence in many countries.

The thing about stagnation is that the scale is enormous. There is a lot of room for there to be harmful regulations which slow technological progress. And there is a lot of room for there to be ways of greatly improving scientific institutions, which you can and should do.

4. GDP is being mismeasured

TFP growth was pretty good between 1994 and 2004, a major exception to the Great Stagnation. Gordon says this is due to the effect of the internet. But, by the time of the book’s writing (2016), he considers the application of the internet to the economy to be mostly complete. He briefly considers the hypothesis that the internet is highly economically useful, but also distracting in a way that offsets the gains, but doesn’t spend much time on it. For a book that contains multiple 100+ page tangents, this is a big omission.

A common retort is that the internet’s contribution to the economy isn’t picked up by GDP. YouTube is free! Wikipedia is free! Blogs are free! Aren’t we living in an age of abundance that can’t be measured by shillings and pence?

The answer to that is: Yes, but less so than we were before. There are several different methods that can be used to estimate the contribution of the internet to GDP, summarised in this piece from the Economist. The most optimistic of them puts the unmeasured gain of the internet at 4% of GDP. 4% is not nothing, but it’s peanuts compared to how much richer America would be if growth maintained its pre-1970 trend. In general, welfare gains went more unmeasured by GDP in the past than today. Increases in lifespan represent half of the total welfare gain from 1920 to 1970, and this isn’t included in GDP (see below).

Robert Solow is famous for the growth model I discussed earlier, but among undergraduates, he is best known for saying funny stuff. One of his better-known quips is that “You can see the computer age everywhere – except the productivity statistics”.

Thus, we really are in a Great Stagnation. While GDP growth is down a bit, actual improvements to welfare are down even more.

Measuring economic welfare is tricky. For the sake of argument, if a TV were as expensive in 1980 as it is today (in inflation-adjusted – ‘real’ – terms), we would not say that consumers are equally well off on this front. TVs today are obviously way better than they were in the 80s. You can attempt to adjust for quality by looking at periods when certain technologies overlap; for example, seeing how much of a premium people were willing to pay for colour TV at a time when black-and-white TVs were still on the market. But the comparisons will be extremely coarse-grained.

Changes in quality are particularly important in the case of houses. By one estimate, air conditioning, heating, and electricity have tripled the value of American houses. This implies that, before the large increase in house prices in the 2000s, modern home buyers were actually getting a much better deal than people in the past.

5. Cultural decline

The Great Stagnation refers to many alleged phenomena, only some of which exist. For example, TFP appears to be growing roughly linearly, so I’m not sure it’s fair to say that technology is stagnating. But one trend that people like Peter Thiel are particularly fond of pointing out is cultural stagnation. There’s just not much of an appetite anymore for great projects. We stopped going to the moon in the 1970s – not because of any blindingly difficult technical challenges, but because of apathy. We used to build monuments to human progress designed to stand for millennia; now buildings are ugly and expedient. Science fiction like Star Trek once painted a picture of a future in which technology greatly improved human life. Now almost all popular sci-fi is dystopian. And so on.

6. Working hours are declining

John Maynard Keynes famously predicted that his grandchildren would have a fifteen-hour workweek. While working hours have been declining almost everywhere, the decline is perhaps less pronounced than you would expect. Unusually for a rich country, American working hours haven’t changed that much since the 1960s. This matters because what looks like a slowdown in economic output could just be people working fewer hours.

Par for the course, Tyler Cowen argues that working hours have not declined more because people like working. Keynes’ grandchildren could have worked fifteen hours per week, if they wanted to have the living standards of their grandfather’s generation. Instead, they buy unnecessary luxury goods and holidays, and send their children to fancy schools.

Comparing work hours across countries is surprisingly difficult, because of differences in reporting standards and work culture. There are certainly stereotypes about how some nationalities work the whole time they are at the office, while others take long breaks and have lots of social activities. The ability to take texts, email and phone calls outside work has increased unmeasured working hours. On the other hand, people slacking off on the internet while at work will lead us to underestimate the time that is, in effect, leisure.

In truth, probably all of these factors are contributing to a degree. But it’s unlikely that they can explain the whole phenomenon.

The growth theory of everything

The last third of the book consists of Robert Gordon giving his loosely related opinions about society.

I gather that the idea here, which he doesn’t quite come out and say, is that many current social problems are downstream of declining economic growth. It is psychologically and culturally important for a people not only to be rich but to be growing.

Growth seems to be healthy for democracy and governance: when the pie is growing quickly, people are not so concerned with who is winning and losing various political fights. But when growth slows, people have a more zero-sum mindset.

Lack of growth is also part of why America has an unusually large underclass for a country of its wealth, which Gordon discusses at length. The problems of America’s most troubled demographics seem to be only loosely related to a literal lack of money. A feeling of despondency and a sense that things are unlikely to improve seem to be key factors. Gordon has a section about all the ways the government shoots itself in the foot and makes this problem worse – especially through occupational licensing and mass incarceration. I couldn’t find figures directly comparing Americans with other nationalities in terms of how licensed they are, but they seem to be on the high end. Anecdotally, the horror stories of the most blatantly protectionist forms of licensing (like requiring a license to be a barber) are disproportionately American. There are plausibly a disproportionate number of Americans kept out of properly competing in the labour market this way.

On the mass incarceration front, a whopping 5% of Americans will be confined to prison at some point in their lives; given the difficulty of getting a job after, it will obviously be challenging to avoid this group becoming a near-permanent underclass.7

Why was there a post-war boom?

Why was the golden age for so many rich economies right after World War II specifically? Gordon says this is one of the most important problems in economic history, and is critically understudied. Somehow, America went from a wartime economy with price controls and rationing to a thriving manufacturing economy with a burgeoning service sector without batting an eye. Many economists at the time predicted that WWII would be followed by another Great Depression. What happened?

A possible answer is that countries get so much poorer during the War that they are starting from a lower baseline, so it’s easier to grow a lot. But Americans got richer from the War, not poorer. One possible lesson here is that machines and factories are surprisingly interchangeable (or at least were in the 1940s).

One consideration is that units and machine parts were standardised earlier in America than elsewhere. The National Bureau of Standards was founded in 1901, which ended up being one of the reasons the manufacturing sector could transfer to civilian use so quickly, while European manufacturing was a mess of non-interoperable components.

Another reason for the boom is that wartime savings were high: America is a historically low-savings society (around 5-10% of income), but the savings rate was 27% during the War. High savings meant high investment, and when the savings rate collapsed after the War, there was a solid few years of profligate spending to stimulate the economy.

Is the Great Stagnation over?

Robert Gordon doesn’t pay his respects to the popularisers of his ideas. Peter Thiel gets a passing mention, and Tyler Cowen isn’t mentioned at all. Perhaps this is because he wants his thesis to be respectable, and not associated with weird techy libertarians.

At times I felt that not even Robert Gordon had read his book the full way through. He is highly repetitive, even to the point of twice telling the same bizarrely specific story about how a British diplomat in Chicago was shocked at how deprived the rustbelt was. It’s as if he expects his readers to have forgotten the start of the book by the time they reach the end. And after 778 tiny font pages, they probably have.

The Rise and Fall of American Growth does not have the obligatory optimistic section at the end in which he discusses how futuristic technologies will release America from economic stagnation. The end of Cowen’s The Great Stagnation is about this; he is at pains to remind people that he does not think the Great Stagnation is inevitable. As with Dawkin’s The Selfish Gene, people all too often read the title, without reading the rather-longer footnote known as the book itself.8

Indeed, it does feel that the future has arrived. We are racing at breakneck speed through the decade of mRNA vaccines and AI girlfriends.

Predictions are hard, especially about the future – but I would be cautious about drawing quick conclusions about the relevance of this to long-run economic history. LLMs are a phenomenal tool, but the scope for distraction and addiction is also immense, and it’s not clear how the effects will net out. Gytis Daujotas writes about his life in the great future of consumer surplus. The future is indeed bright for the small number of super-performers like Gytis. He lives in San Francisco, where he presumably often walks by homeless people, whose lives are not being improved one iota by AI. Innovation being rapid and transforming your life is entirely compatible with an economic picture that is mixed.

I am about three years late to the party on this, but both sides of the debate over whether stagnation was ending during and after the pandemic were having completely different conversations (“I don’t think it’s controversial to say that the pro-stagnation evidence was of dramatically higher caliber… But today, all it takes is some guy tweeting out a few bullet points, and everyone loses their minds.”). Some, like Gordon, are interested in the relatively niche economic history question of why productivity improvements have taken the shape that they have. Others are interested in what you might call the ‘vibes stagnation’: a general perceived sense of cultural malaise and lack of ambition. These two things are only partly related. At the risk of being a killjoy, while the vibes do seem to be awaking from their slumbers, the relevance of this to economic history is more questionable.

I share Patrick Collison’s intuition that we ought to be obsessed with these questions of comparative rates of progress, growth, and innovation. We will passionately squabble about how to fund or distribute education or healthcare, with few stopping to ask why these things cost so much more than they used to for the same or worse product. Some times and places are dramatically more economically, scientifically, and culturally more productive than others; we ought to be obsessed with why. When you start thinking about stagnation, it’s hard to think about anything else.

Sam Enright is executive editor of the Fitzwilliam. You can follow him on Twitter here or read his personal blog here.

TFP is only assumed to measure improvements in technology. It’s actually that which is left over in output after accounting for labour and capital and their respective elasticities. TFP is also called ‘Solow’s residual’ for this reason. Note that when someone like Gordon talks about ‘technology’, they mean it in an expansive sense, which includes things like improvements to management practices. It’s possible that a more technologically capable society would have a lower TFP due to bureaucratic and inefficient firms.

Why the absolutely massive spikes in Britain, twice in Japan, and in Ireland? The data are noisy and may be poor quality, so I wouldn’t think too hard about it. The two nosedives in Japan may correspond to the Kantō earthquake and the destruction of WWII.

I really don’t want to get bogged down in the details of the Bloom et al paper; there are substantial criticisms of it, and I am in no position to defend it. I think the answer to their titular question is yes, but under a counter-intuitive and perhaps unreasonable definition of ‘ideas’. I really am not trying to defend any specific view of what should count as an ‘idea’ from the perspective of growth economics. My argument is much more intuitive than that.

I am describing the basis of the Solow-Swan model.

Chapter 7.

Using an admittedly weird definition of ‘productive’! In the model of Bloom et al (the paper discussed in the Scott Alexander essay), an ‘idea’ results in a fixed percentage improvement in some process.

Note that this figure comes from a paper from 1997; I couldn’t find a more recent figure that included this ‘lifetime risk’ calculation.

I am contributing to this problem, in that I haven’t read The Great Stagnation either (sorry!).

I would agree with 5. Cultural decline and 3. Excessive regulation (at least in the west). In 5 minutes I could find several examples where regulation is (insanely) stifling innovation

1. SpaceX starship being delayed by nearly year because of “Environmental Review”. (It’s in the middle of the desert?)

2. FDA stifling innovation: https://sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/the-death-of-jesse-gelsinger-20-years-later/

Is the so-called “Faustian Spirit” (https://counter-currents.com/2013/06/the-faustian-spirit/) still well and alive in Europe? I often think of the Tibetans being confused as to why anyone would attempt to climb Everest. "Because it's there." - Mallory.

I would contend with 6. Working hours are declining. The hours being put towards productive tasks as opposed to just surviving must be greater in aggregate when you factor in India, China etc…

I saw Fergus “restacked” your post. I would be inclined to agree w/ him that University and how research is conducted is significantly to blame. In short

+ Peer Review (Einstein famously insulted by peer review) sucks. Watch this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yckPYJgjXeY. A math prof writes a paper in ~ 2 months. Takes nearly 2 years to get published. Compare this to how much work was achieved in weeks, when the superconductor paper was published on arXiv. We need to shorten feedback loops

+ Research Agencies/ Grant Agencies. See the effect your mates Patrick/Tyler had with fast grants vs NIH, NHS etc…(Anything groundbreaking in the past 100 years is near guaranteed to be have funded by DARPA. It’s budget is only ~4 billlion!)

+ Wrong incentives in Academia only way to climb is become an Administrator and empire build taking on grad students doing iterative work.

+ More places nowadays for the insanely talented to go vs the Victorian Era. Would Maxwell be working in a Hedge Fund nowadays?

I would highly recommend the below, Great Post Discussing what’s gone wrong in Academia:

https://jameswphillips.substack.com/p/ucl-talk-government-science-and-the

This is a fantastic overview of the stagnation debate, and almost fully on the nose. I must disagree with one thing, namely the “ideas are harder to find” section. How could one even judge such a thing, without knowing what discoveries are lying ahead (which we can’t, per definition). I forgot who it was that lamented that he wished he lived before Newton, since the laws of physics could only be discovered once. Of course, he was proven wrong by Einstein. There is no reason to assume that reality is not infinitely complex, and there’s always much more to discover. Any lamentation such as the above seems ridiculous in hindsight, and people lamenting it now will seem ridiculous in 500 (or even 100) years.

The same thing goes for economic growth. The thing which degrowthers consequently get wrong with the “infinite growth is impossible on a finite planet”-quip is that growth does not need to be quantitative, but can be qualitative as well (e.g. colour television instead of black and white television). Since we can find better ways of producing things with less resources, and since people pay more money for better products, we can keep improving the human condition infinitely of a finite planet.

Moreover, as you point out, there are always more S curves out there that we can climb. Looking at the ones we currently know of, and saying that they are running out and as such progress must end, is just failure of the imagination (and of studying the history of science). The big society moving breakthroughs are almost always fundamental to such a degree that they they create their own new paradigm. This is why the # of researchers is far less relevant than the amount of researchers working on fundamental, interdisciplinary, contrarian and daring research.