Who Cares About Bogs?

The complex story of Irish peat

The bogs of Ireland are landscapes of labour, ecology, and history. They were once great vessels of water which naturally absorbed carbon from the atmosphere, and served as the habitat for some of the rarest plant and animal species in Europe. But almost all of Ireland’s bogs have been transformed, over centuries, for subsistence and economic gain. Recently, bogs have been drawn into debates about nature restoration, tradition, and climate change – and not without controversy. Bogs have been, and continue to be, the subject of a peculiarly Irish culture war.

Despite how common they are, most Irish people will never set foot (or welly) into a bog. In the wider public imagination, they are picture-postcard places from a bygone era, often associated with backwardness and poverty. But for many in rural Ireland, boglands, and the peat derived from them, are a part of everyday life. The ‘saving’ of turf in the late spring and summer months is part of the social fabric of western and midland communities. The resulting harvest provides a cheap and sweet-smelling fuel that warms tens of thousands of homes during the winter. One in seven Irish households still burns peat for heat.

The features which people value in bogs are not always compatible – a confusion which has also been reflected in public policy. But first, let’s define what a bog actually is.

The geography of bogland

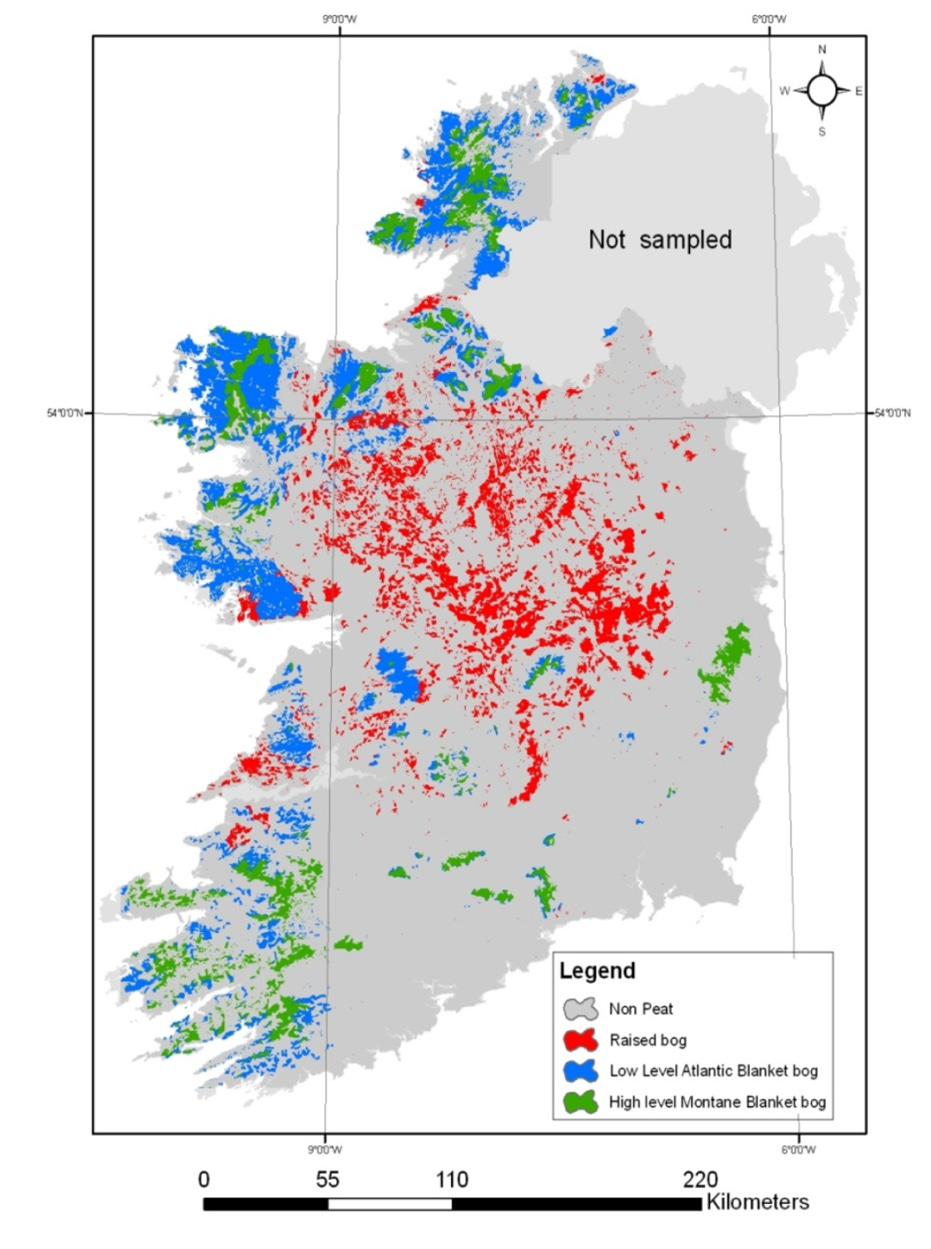

Peatlands, like swamps, marshes and turloughs, are types of wetland. Across the entire world, peatlands contain 10% of the planet’s freshwater. Almost 15,000 km2 of the Republic of Ireland is covered by peat soils, around 20% of its total surface area.1 Northern Ireland has almost 3,500 km2, or 25% of surface area.2

There are two main types of peatland in Ireland: bogs and fens. Fens are wetlands with a permanently high water level, which receive their nutrients from direct contact with surface or groundwater. Water slows the decomposition process of organic material, which eventually turns into peat.

Fens are the precursors to raised bogs. They are now very rare in Ireland, having transformed naturally or been ‘reclaimed’ for agricultural use.

In contrast to fens, bogs receive all their moisture through rainfall. There are two types found in Ireland: blanket and raised. Blanket bogs are shallow when in mountainous areas, at around two metres in depth, while in lowland regions they can reach up to seven meters.3

Raised bogs are mostly found in the midlands. Once enough peat accumulates within a fen, any additional groundwater is diverted around the perimeter. With rain now the only source of moisture, the peatland becomes increasingly nutrient deficient and sphagnum mosses begin to dominate. The ecosystem turns acidic. As sphagnum and other species grow and die off in the anaerobic conditions, they will turn into peat. This process is extremely slow, with each metre of bog taking a thousand years to grow. Raheemmore bog in east Co. Offaly is the deepest bog in Ireland at fifteen meters, although most do not exceed ten. Raised bogs are the rarer of the two. Ireland has more than half the European Union’s remaining area of Atlantic raised bog, which is one of the world’s rarest habitats.

The waterlogged conditions of bogs are what lead to another of their celebrated properties: the ability to preserve, for thousands of years, organic material which would ordinarily decompose. Archaeologists have found bog bodies from as far back as 8000 B.C., which can still have preserved hair, nails, and internal organs. Our knowledge of the health and physiology of prehistoric people disproportionately comes from bogs.

Turf-cutters, the bogs, and the state

Europeans have cut sods of peat (known as turf) for centuries. The earliest records of the use of turf for fuel are from the 7th century. Ancient Irish legal texts contain evidence of the widespread use and regulation of turf.

In the 19th century, the Russian Empire initiated wetland drainage in Polesia, a region straddling the borders of Belarus, Ukraine and Poland, to encourage development in the ‘backward’ hinterland.4 Today, more than half of Belarussian peatlands have been drained, with almost three-quarters of the drained land being used for agriculture.5 Small-scale cutting has been closer to the centre of the Irish relationship with bogs than in Eastern Europe. By some estimates, 40% of Irish peatlands have been degraded as a result of domestic cutting, exercised through rights of 'turbary’.6

Turbary rights provide the legal basis to cut peat from a given bog.7 These are complex arrangements, and ownership is often difficult to prove. In my own research about bogs, I’ve found that those who visit their bogs infrequently can easily forget where their turbary actually is.

Turf-cutting begins in spring, usually in the days and weeks on either side of St. Patrick’s Day. A tool called a sleán was used in the past to extract turf from the face of the bog. The bog was prepared beforehand by draining and removing vegetation; extraction consisted of several people, often families, labouring together. The freshly cut turf was transported via wheelbarrow to an area nearby known as a spread bank.

Peat holds a tremendous volume of water. After it’s cut, it’s baked in the sun to dry (this part of the process remains the same today). As the turf dries, it is stacked in such a way as to enable the wind to aerate it until it is solid enough to be transported and stored in its owner’s home. This whole process is called ‘saving’ turf.

Turf is rarely cut by hand anymore. Instead, those with turbary rights hire local contractors to dig out their plot with an excavator. Turf-cutters continue to manually turn and stack their harvest, known as ‘footing’, until it’s dry, as they have done for generations.

Irish bogs have not just been subject to domestic use. Peat has been extracted commercially, with mixed results, since the mid-19th century.

Bord na Móna

From the 1930s, the semi-state company Bord na Móna (‘The Peat Board’) extracted peat from Irish bogs on an industrial scale. Bord na Móna was formally established under the Turf Development Act 1946, as the successor to the Turf Development Board, a state-owned company set up twelve years previously to oversee the development of Irish peat. The firm’s remit was to produce an indigenous source of fuel for the nascent Irish Free State, while employing people in otherwise underdeveloped parts of the country. It was a similar development strategy to the one pursued by the Russian Empire a century earlier.

Bord na Móna evolved through a series of legislative changes and development programmes. The first involved the mechanisation of turf extraction. Cutting turf by hand was laborious and generally not commercially feasible. Large German-manufactured machines called baggers were first introduced to the Clonsast Bog Group, in east Co. Offaly, in 1939. Although efficient, baggers were prone to frequent breakdowns. At 35 tonnes, they were too heavy for the wet conditions in Ireland and frequently sank into the bogs.

Operations at Bord na Móna were expanded under the Turf Development Act 1950. This involved a transition to milling peat as the primary method of extraction. Baggers cut down into the bogs and extruded turf sods across its surface. But this new production method involved agitating peat on the surface of a drained bog – loosening it and exposing it to the air until it was dry.

To transport peat, Bord na Móna owned and operated an extensive railway network. It used a 3ft narrow gauge, compared to the 5’3” gauge of normal Irish passenger rail. Bord na Móna’s tracks made up one of the largest industrial railway systems in Europe – and, at its peak, spanned more kilometres of track than all other freight and passenger railways in Ireland combined. The board used both road and rail to transport peat from bogs to the users.

In addition to supplying the Electricity Supply Board (Ireland’s state-owned electricity company), Bord na Móna operated four briquette factories, a single power station, and three moss peat processing and packing plants. Briquettes offered retail customers a cleaner and more convenient alternative to turf sods. Bord’s last briquette factory, located in Co. Offaly, closed in June 2023. Moss peat, which comes from the upper layers of a bog, was sold into the horticulture market for use as a soil conditioner. Moss peat was a high-volume and low-profit enterprise, but one which arguably had the strongest economic viability of any product supplied by the board.

Another major Bord na Móna development programme commenced in the mid-1970s. The company expanded its operations into previously uneconomic peatlands in response to the global oil crisis. In so doing, Bord na Móna thought it was fulfilling its mandate to provide a secure supply of energy to Ireland. Yet this would lead to a financial crisis in the company during the mid-1980s as alternative energy sources once again became cheaper on the world market. This had major consequences for peat-dependent communities and the state itself, which would ultimately bail out the company.

The declining peat sector

In September 2019, in a court case brought by Friends of the Irish Environment, an Irish High Court judge deemed that peat industry regulations were incompatible with European Union environmental impact assessments. From that point on, extraction of peat on sites larger than 30 hectares was effectively banned. This ruling hastened the demise of Bord na Móna’s peat extraction activities, which were already slowing.

In January 2021, Bord na Móna announced that it would stop cutting peat entirely. This was met with a range of emotions. Environmental campaigners welcomed the end of the board’s environmentally damaging enterprise. However, by one estimate, it extracted peat from just 3.4% of Irish boglands.8 Turbary and land reclamation for agriculture has had a much larger negative environmental effect.

There were also widespread concerns about the people made redundant from peat production. The Irish government’s Territorial Just Transition Plan provides the most accurate estimate of the number of people affected: around 1,000 workers lost their jobs from bog closures between January 2019 and May 2021, with around 350 workers redeployed in short-term roles rehabilitating cutaway bogs (another name for bogs which have been extensively harvested for peat). These recent job losses are dwarfed by those let go from the mid-1980s onwards.

In his account of the Irish peat industry, former Bord na Móna secretary Donal Clarke provides historical data on the number of workers in the company. In 1983, peak employment was 7,171 across both seasonal and permanent workers. From here, job loss was precipitous. By 1992, just 2,767 workers were employed during peak production. This was the response of the managing director Eddie O’Connor to the financial difficulties that the company found itself in after overstretching its operations in the 1970s. Numbers employed only decreased slightly year-on-year until the present day.

During the research for my PhD, one employee remarked to me that working for Bord na Móna, in his day, was “a very big identifier in [the midlands]. It gives people standing that you’re part of Bord na Móna – part of something bigger than yourself.” In the 1980s, O’Connor reconfigured employment practices in Bord na Móna to great effect, after he commissioned a comparative analysis which showed that Irish workers were only producing half as much peat as their Finnish counterparts.9 The new system offered more autonomy and gave workers rewards for increases in productivity. But ultimately, the economic challenges of peat extraction on ever-dwindling bogs were mounting. Around the same time, new visions were emerging for the future of bogs.

Wasteland or wonderland?

The bogs as wastelands narrative which enabled their destruction began to be challenged in the latter half of the 20th century. Bord na Móna employee Thomas A. Barry argued in 1976 that “At some future date unless prompt and resolute measures are taken, there will be no undrained bog left.”10 Barry’s advocacy led to the preservation of the aforementioned Pollardstown fen and Raheenmore bog. A survey in 1990 concluded that there were no completely intact raised bogs remaining in Ireland, and that degradation was occurring at a rate of 3,500 hectares per year.

The environmental role provided by bogland has since become widely known. Bogs contain a diverse range of specifically adapted flora and fauna including the carnivorous plants sundews and bladderworts. Red grouse, curlew, snipe, Greenland white-fronted goose, and hen harrier are just some of the rare birds found in peatlands. More recently, bogs’ carbon sequestration and storage capabilities have become widely discussed. It has been estimated that Irish bogs store over 2.2 billion tonnes of carbon, the equivalent of 36 years of emissions from Ireland.11

Efforts to protect bogs for environmental reasons have proven contentious, hitting at the heart of urban versus rural tensions. The designation of some notable bogs as Special Areas of Conservation under the Habitats Directive in the late 1990s was a particularly controversial episode. Turf cutters were ordered to halt extraction with little notice and without the offer of compensation. They organised and resisted. The government relented and unilaterally gave those affected a ten-year exemption, effectively permitting a further decade of ecological destruction.

The Irish government’s failure to enforce the Habitats Directive has brought it into conflict with the European Union. It’s hard to find a politically acceptable way to regulate peat. In 2022, the commercial sale of turf was banned by the state to protect air quality. This, again, was met with considerable controversy and pushback. Illegal turf-cutting to evade these regulations continues to some extent, but there recently has been renewed cooperation across government and turf interests to finally bring this to a close.

The aftermath of industrial extraction

Bord na Móna has pivoted its operations towards more sustainable business practices as part of a strategy it calls Brown to Green. It commissioned Ireland’s first wind farm in 1992 and has continued to roll out renewable energy infrastructure on cutaway bogs since. But some local citizens’ groups have opposed the construction of new wind farms on boglands. Bord na Móna was initially granted planning permission for 24 wind turbines in Longford, but this was later overturned in a High Court challenge. As is often the case, Ireland gets in its own way in pursuit of environmental goals.

In addition, 33,000 hectares of cutaway bog are the subject of ‘enhanced’ rehabilitation under the European Union and Irish state-funded Peatlands Climate Action Scheme. The plan is to use advanced measures to stabilise and restore former industrial bogland for use as carbon sinks.

Efforts have been underway in Canada, Germany and Belarus for over a decade to cultivate crops on peatlands. In a process called ‘paludiculture’, degraded peatlands are rewetted to reduce carbon emissions, and planted with commercially valuable species such as sphagnum moss.12 Its rollout in Ireland has been limited to just one project, the ongoing Farm Carbon European Innovation Programme. Further research on this technique is required in Ireland, but in any case, its widespread implementation on Irish bogs would come too late for the workers recently made redundant.

It turns out lots of people care about bogs.

Extraction has dominated Irish people’s interactions with bogs for centuries. Contemporary efforts to conserve what remains of them have clashed with tradition. Yet attitudes towards peatlands are subject to change. I’m optimistic that peat workers will accept new jobs that do not harm the environment, and that turf-cutters are willing to concede their carefully guarded turbary rights if they see themselves to be compensated fairly.

The Irish government’s response to the shutdown of industrial bogs has been rushed due to the sector’s abrupt closure. Over €300 million has been, or will be, invested by the Irish state, Bord na Móna and the European Union to rehabilitate these lands and (one hopes) offset economic decline in midland communities.

These efforts may be belated, but there is still time for an equitable transition. The history of environmentalism offers the occasional grounds for optimism (like with acid rain, or CFCs). The potential for bogs is less widely known, but it is enormous. I do not know whether plans for the just transition of bogs will succeed – but I know that they can.

Jamie Rohu lectures in environment studies at Dublin City University and holds a PhD from Trinity College Dublin about the just transition of Irish bogs. You can follow him on Twitter here.

This figure and the map come from Connolly, J. and Holden, N. M. 2009. Mapping peat soils in Ireland: updating the derived Irish peat map, Irish Geography Vol. 42 No. 3 pp. 343 – 352.

Lindsay, R. A. and Clough, J. United Kingdom, in: Joosten, H., Tanneberger, F and Moen, A. (eds.) Mires and peatlands of Europe – Status, Distribution and Conservation Stuttgart: Schweizerbart Science Publishers, pp. 705-720.

NPWS, 2013. The status of protected EU habitats and species in Ireland. Overview Vol. 1. Unpublished report, National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Dublin, Ireland. Editor: Deirdre Lynn.

Bruisch. K. 2019. The State of the swamps: Terriorialization and Ecosystem Engineering in the Western Provinces of the Late Russian Empire. Journal of East Central European Studies. Vol. 68, No. 3, pp. 345-368.

Tanovitskaya, N. 2011. Peatlands in Belarus - Use of Peatlands and Peat, in: Tanneberger, F. and Wichtmann, W. (eds.) Carbon Credits from Peatland Rewetting, Stuttgart: Schweizerbart Science Publishers.

Foss, P. J. and O’Connell, C. 2017. ‘Ireland’, in: Joosten, H., Tanneberger, F and Moen, A. (eds.) Mires and peatlands of Europe – Status, Distribution and Conservation Stuttgart: Schweizerbart Science Publishers, pp. 449 - 461. This was also my source for the ‘earliest record of the use of turf for fuel’ claim.

Feehan, J. O’Donovan, G., Renou-Wilson, F. and Wilson, D. 2008. The Bogs of Ireland – An Introduction to the Natural, Cultural and Industrial Heritage of Irish Peatlands Revised Edition. Dublin: University College Dublin.

Connolly, J. 2018. Mapping Land Use on Irish Peatlands Using Medium Resolution Satellite Imagery. Irish Geography Vol. 51, No. 2, November 2018.

O’Connor, E. 2021. A Dangerous Visionary Dublin: Currach Books.

Barry, T. A. 1976. Environmental protection and the bogs of Ireland. Fifth International Peat Congress, Poznań, Poland.

Based on 2022 figures. See Renou-Wilson, F., Byrne, K. A., Flynn, R., Premrov, A., Riondato, E., Saunders, M., Walz, K. and Wilson, D. 2022. Peatland properties influencing greenhouse gas emissions and removal. Environmental Protection Agency, Report No. 401, Ireland, and EPA, 2023. Ireland’s Provisional Greenhouse Gas Emissions, 1990 - 2022. Environmental Protection Agency, Ireland.

Wichtmann, W., Schröder, C. and Joosten, H., 2016. Paludiculture as an inclusive solution, in: Wichtmann, W., Schröder, C. and Joosten, H. (eds.) Paludiculture - Productive Use of Wet Peatlands Stuttgart: Schweizerbart Science Publishers, pp. 1-2.