Peru, my home country, is notorious for corruption. The intuitive solution, often proposed by national political figures and international organizations, is to enact better anti-corruption reforms. Yet countries with high levels of corruption, like Peru, are the least scared of reforms. Every few years, the latest political administration promises to finally put an end to this problem and enact a new series of anti-corruption initiatives. Many of these have indeed become reality, but the situation remains grim.

Peru’s leaders are comically crooked

Peru became independent from the Spanish in 1821. Between then and 1979, the government alternated between militarism and democracy countless times, and went through nine different constitutions. The 1979 constitution was intended to serve as the final transition to democratic governance. This constitution extended suffrage to all adults by eliminating the literacy requirement for voting, limited the president to a single five-year term, established a right to civil disobedience, reduced the excessive parliamentary powers provided by the previous constitution, and proclaimed the country a “social democratic state”.

Even though presidents are supposed to serve five-year terms, Peru has managed to have ten since the turn of the century, each more corrupt than the last:

Alberto Fujimori

The “final” Peruvian constitution lasted only until 1993 when Alberto Fujimori, then-president, deemed we needed a more market-friendly one. Fujimori’s constitution reintroduced presidential reelections, a unicameral congress, the death penalty, and referendums. Our current president, Pedro Castillo, is thinking about replacing it again. This sort of thing is relatively easy in Latin America, where weak court systems are often staffed with the president’s cronies.

Valentín Paniagua

After Fujimori—currently in prison for human rights abuses—was removed from the presidency following a corruption scandal in 2000, Valentín Paniagua became acting president for a brief transitional government. Paniagua established the National Anticorruption Program and the National Anticorruption Initiative working group. These groups aimed to pursue a thorough analysis of corruption in the country and create a national agenda to tackle it.

Alejandro Toledo

Alejandro Toledo was elected in 2001, and with the National Anticorruption Initiative’s work now complete, his administration formed the National Anticorruption Council to craft policy for preventing corruption and set up the Directorate Against Corruption of the National Police of Peru. Yet last year, a judge approved Toledo’s extradition from the United States after he fled Peru due to corruption allegations, and he was sentenced to prison for having received 20 million USD in bribes.

Alan García

Alan García—who had been president before Fujimori and led the country to serious hyperinflation—was elected for the second time in 2006. His Ministry of Justice presented the National Plan for the Fight Against Corruption with seven objectives and nineteen strategies to achieve them, which became national policy. The plan included increasing transparency in the administration of justice, developing a culture of ethics in society and the business sector, increasing accountability, and increasing transparency in public administration. The executive power refounded the High Level Anticorruption Commission, and tasked it and the Multisectoral Working Group to implement the plan.

García shot himself in the head in 2019 after police entered his house to arrest him for money laundering and—of course—accepting bribes during his second presidency.

Ollanta Humala

The next president, Ollanta Humala, was elected in 2011. Among other reforms, he passed a law establishing the culpability of companies for international bribery crimes. He ended up serving nine months of jail time and is currently awaiting trial, where, in true presidential fashion, he and his wife are facing up to 20 and 26 years in prison respectively for accepting bribes from the Brazilian conglomerate Odebrecht.

Pedro Pablo Kuczynski

Pedro Pablo Kuczynski was elected in 2016. His government passed the Corporate Corruption Act, which holds legal entities such as corporations liable for corruption for the bribery of public officials in Peru. He is currently under house arrest as he is being investigated for corruption. He didn’t even get to finish his term, as he had to step down from the presidency in 2018 due to a completely unrelated corruption scandal.

Martín Vizcarra

After Kuczynski stepped down, his vice president Martín Vizcarra took office. Vizcarra implemented a series of popular anti-corruption measures that were passed by referendum, including banning the private financing of elections, and he was impeached in 2020 in an extremely unpopular decision that was widely perceived by the public as retaliation by Congress. But public opinion quickly turned against him after a scandal known as “vaccinegate”, in which news broke that he and other members of the Peruvian executive had been vaccinated against COVID-19 in secret before the country started its vaccine rollout.

Manuel Merino was sworn in as president after the controversial impeachment, and lasted only five days before stepping down due to overwhelming protests. Francisco Sagasti replaced him and served as the interim president until the 2021 elections, and Pedro Castillo has been president since.

How is Peru (still) so corrupt?

What is striking about this history is not just the appalling, almost comical, hypocrisy of political leaders, but the fact that anti-corruption reforms and initiatives don’t have much to show for themselves.

Peru’s score on the Corruption Perceptions Index has fallen two points since 2012, sitting at 36/100, where a score below 50 indicates “serious corruption problems”. In 2018, 19 out 25 Governors were being investigated for corruption in 158 different cases, as well as 92% of mayors. Corruption in the country includes not just elected officials, but the police, hospitals, the media, schools, and the private sector. And it is not just in the form of money—around 10% of Peruvians say they or someone they know has asked or been asked for a sexual favour in exchange for solving a problem.

According to a 2019 survey, 62% of Peruvians point to corruption as among the most serious issues facing the country (led only by crime), a share that has been steadily rising since 2002. Eight out of ten Peruvians say corruption negatively affects their everyday lives, 73% believe corruption has increased in the past five years, and 40% believe it will continue to increase in the next five. Those who are most concerned about corruption are the most educated, who tend to be more knowledgeable about the government’s inner workings. People are so desperate that, in an attempt at populism, congress members have gone so far as to propose bringing back the death penalty for corruption.

On the one hand, there are positive indicators. The staggering rates of politicians being investigated and imprisoned means the acts of corruption were caught, deemed impermissible by the law, and prosecuted—in a sense, the system is working. Despite this, the effect on actually reducing corruption has been minimal. Why?

Corruption persists for deep structural reasons. As one notable paper on the topic puts it, “...in a context in which corruption is the expected behaviour, monitoring devices and punishment regimes should be largely ineffective since there will simply be no actors that have an incentive to hold corrupt officials accountable.”

The short-term costs of refraining from corruption are very high—it is difficult to succeed in a system if you are refusing to cooperate with and participate in the behaviours of your peers. It would be difficult for someone to reach or keep the presidency in Peru without engaging in egregious corruption.

The most common forms of corruption in Latin America are blatantly illegal, and corruption among elected officials is frequently prosecuted. This contrasts with the dynamic in developed countries, where the unscrupulous behaviours politicians engage in primarily take place through technically legal means. Corporate lobbying and dubious campaign financing are widely perceived by the public as corrupt, but are ultimately legal. Cases of blatantly illegal corruption are much rarer.

Legal and illegal corruption are two very different styles of malfeasance, and perhaps in countries where elected officials are more likely to stick to the law, more stringent legislation makes sense. But in countries like Peru, the anti-corruption legislation passed in the past few decades is almost irrelevant because no one in power ever seriously intended to abide by it. Peruvians have—understandably—lost faith that the next Congress or administration will finally end endemic corruption, and this is not an isolated example. The 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index report notes that “Despite multiple commitments, 131 countries have made no significant progress against corruption in the last decade.”

Is there hope?

What is the solution for countries where corruption is already criminal, frequently prosecuted, and yet still endemic? Can anything be done, or is this too deeply ingrained in the culture of an absurdly amoral political elite?

Peru’s legal setup is far from perfect, and certain reforms are clearly necessary and important. The counsellors that appoint and remove judges must be vetted more thoroughly for conflicts of interest and criminal records. Political parties must be strengthened—they are currently extremely unstable and essentially ideologically baseless.

It is possible to create meaningful change by putting a new government in charge to make reforms — it happened, for instance, in Georgia. But it is very difficult, and most Peruvians have become cynical about it happening anytime soon. Luckily, it may not be the only tool in our arsenal to combat endemic corruption.

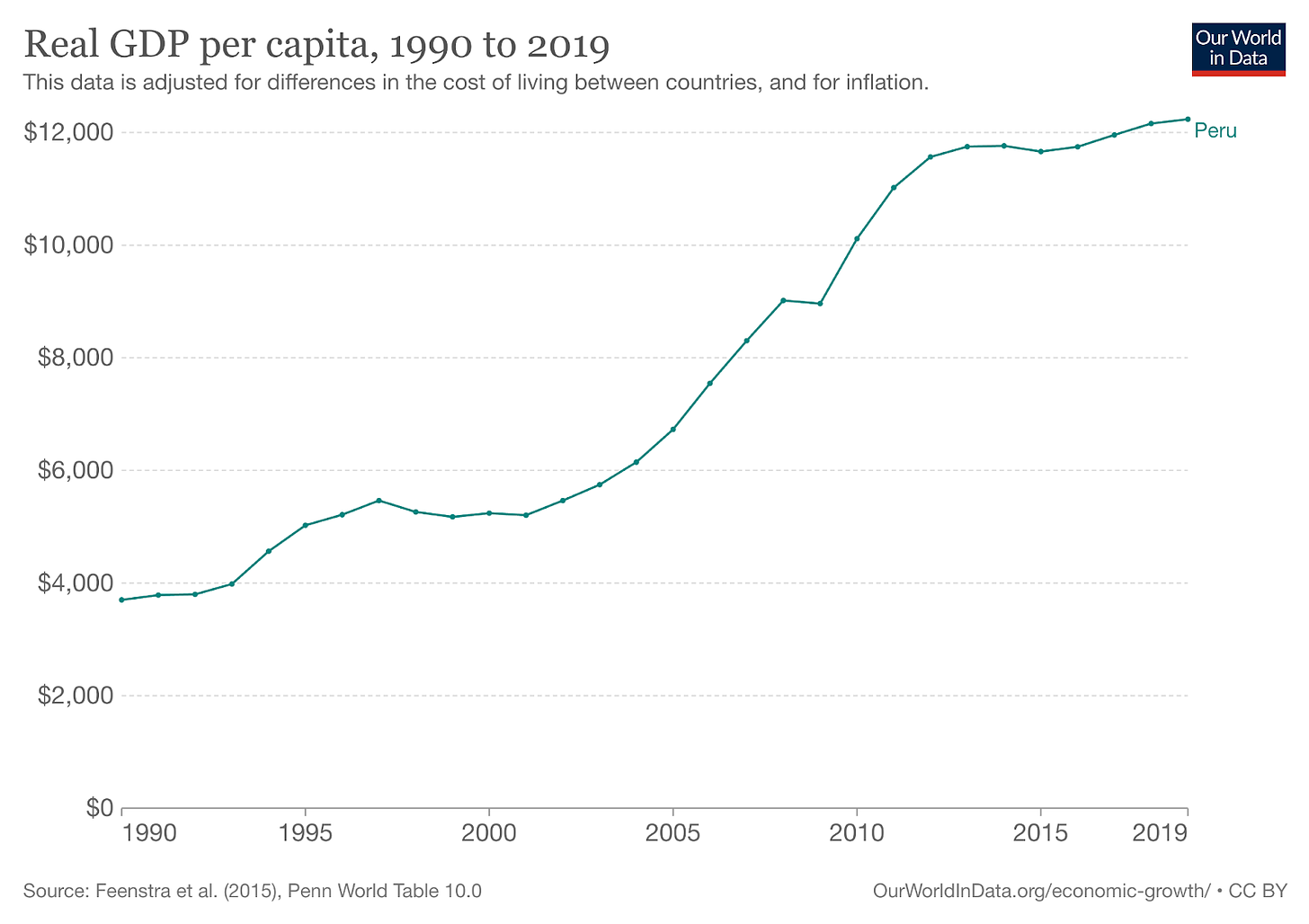

Despite its history of atrocious governance and political instability, Peru has somehow managed to maintain decent levels of economic growth. GDP has been steadily rising since the 1990s, and we have seen an influx of foreign companies that were too scared to invest in the country previously during the ‘era of terrorism’.

Despite having one of the longest and strictest COVID-19 lockdowns in the world—with schools only reopening this March—Peru’s GDP growth rate is projected to quickly recover to its pre-pandemic level of around 3.4%.

Peru was called a “rising star” by the IMF in 2011 due to its steady annual growth, low inflation, and general economic stability over the past 20 years, with some having upgraded the country’s classification to middle-income. Our human development index has also risen from just above 0.6 in 1990 to 0.77 in 2019.

This is impressive for such a politically chaotic country, but it does not imply that the aforementioned history has not interfered with our progress—Peru has been able to achieve this economic success despite the destructive effects of corruption on economic growth.

In addition to the implications for quality of life, this economic prosperity should also provide Peruvians with hope for another reason. There is some evidence that suggests there is a causal relationship between economic growth and corruption—as a country becomes richer, corruption decreases. Corruption appears to rise initially as countries get a little bit richer, then fall as they get richer still. Economist Simon Kuznets famously proposed that, as countries get richer, inequality would first rise and then fall, in an inverted U-shape. Some researchers have proposed a kind of corruption Kuznets curve.

There are a few mechanisms that could be responsible for this. As companies grow, they become more powerful and less dependent on a given government, reducing their need to participate in risky practices or succumb to requests for bribes. Meanwhile, government employees and elected officials experience a reduced sense of scarcity, and the risks of illicit activities may no longer be worth it—the relationship between poverty and crime more generally is well-documented. There could also be some cultural effects of economic development at play—as people get richer, they don’t look as much to socially destructive ways to extract rents from others.

This mechanism is still relatively under-researched compared to its converse—corruption influencing economic growth—but it seems promising.

Chile and Uruguay, the two countries in Latin America with the lowest levels of corruption, are also the two with the highest GDP per capita, which also suggests that this may be part of the solution. How they got there is much harder to generalize—for instance, Uruguay was known to Spanish colonizers as the “land of no profit” due to its lack of precious metals or cheap indigenous labour, making the country immune to the resource curse and warding off oligarchs. A previous Fitzwilliam essay about Haiti discussed exactly such ‘reversals of fortune’.

Various other factors have been found to reduce corruption, such as democracy, growth, trade openness, political stability, and economic freedom. Peru does relatively well in the latter department—it is classified as “free” on Freedom House’s index of political and civil liberties and has an economic freedom score higher than the world and regional average. But, as you have noticed, it struggles significantly with political stability. Press freedom has also been found to decrease corruption, and Reporters Without Borders has given Peru a “problematic” score of 61.75 out of 100 for it, only somewhat better than the median.

To the extent that Peru has been performing well on economic growth, trade openness, democracy, and freedom over the past couple of decades, the effect on corruption hasn’t been drastic. But if the relationship between these and corruption holds any truth, then even if Peru is unable to elect principled leaders, it may still see progress.

Inés Fernández is a computational social science student at University College Dublin. She has previously conducted research for The UBI Center, the Alliance to Feed the Earth in Disasters, and SoGive. You can follow her on Twitter here.

"The staggering rates of politicians being investigated and imprisoned means the acts of corruption were caught, deemed impermissible by the law, and prosecuted—in a sense, the system is working."

This may not necessarily mean the system is working. It could equally mean that the system is unjustly and corruplty pursuing previous power-holders in an act of political vengeance and self-promotion!

Thanks for this great post.

My model had been that a main driver of corruption was the social expectation of corruption – basically the idea you quoted + the power of default behaviors and inertia:

“...in a context in which corruption is the expected behaviour, monitoring devices and punishment regimes should be largely ineffective since there will simply be no actors that have an incentive to hold corrupt officials accountable.”

Until reading this post I hadn't realized that this model doesn’t do a good job explaining the recent corruption in Peru though. There’s apparently enough accountability for Alan Garcia to kill himself rather than face up to it – that seems like a pretty well functioning accountability mechanism! The other corrupt politicians you list seem to be facing real accountability as well.

One way of reconciling this could be:

• The social expectations about corruption that are driving the current accountability mechanisms have emerged relatively recently (say over the past ~20-30 years)

• This batch of corrupt politicians grew up and absorbed more permissive social norms about corruption that existed prior to the emergence of the new ones.

• Their corrupt behavior reflected the prior permissive norms but was then met with the accountability from the new less-permissive norms.

This explanation would also be consistent with:

(1) More reported social concerns about corruption (because people care more about it)

(2) Higher reported corruption levels (more is being caught and reported because people care more about it)

Hopefully I’m not being too optimistic :)